Experiencing a Coup from Afar

It is the 7th of December 2025. I have been preparing my research project in Benin for several months and am scheduled to leave in about a month. It is early in the morning when a breaking news notification flashes on my phone. Al Jazeera: “Coup d’état attempt in Benin.” Before I can fully process it, other alerts begin to appear on my phone: headlines, updates and videos, one after another. Almost immediately, I open multiple news outlets, both local and international, hoping to find clarification. Yet little information is available. Reports are brief, repetitive and fail to fully describe the situation. There are no details and no confirmations, so instead I turn to social media. I move from Facebook to TikTok, from Instagram to X, searching for that extra piece of information that could definitively explain what is actually going on.

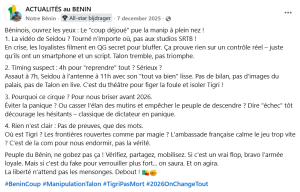

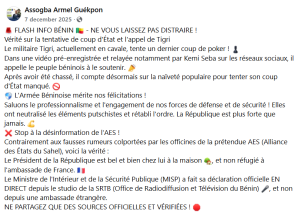

Instead, I encounter chaos. Narratives multiply rapidly and contradict each other entirely. Some posts dismiss the coup as a complete deception. Others announce that it has already succeeded. Some claim the president is safe and under protection; others insist he has been captured, or even killed. The stream of updates is continuous, each telling a different truth. For several hours, I linger in confusion. I worry about people in Benin and those I have been in contact with, as well as the implications for my research project. During these hours, all I do is scroll and refresh, trying desperately to find the newest information that could tell me what is actually happening. But the constant flow of information does not relieve the uncertainty; it only worsens it.

Only after half a day does the smoke begin to clear. Gradually, one narrative becomes the most dominant: the coup attempt appears to have failed, and the situation seems to be under control. Not long after, the president delivers a televised speech, officially confirming that this is indeed the case. I stop refreshing social media feeds obsessively, feeling relieved but also puzzled. During those first hours after the coup attempt, so many conflicting narratives circulated online that making sense of the situation felt nearly impossible. How is it possible that such an abundance of information could result in so much confusion? And what must it have been like for the nearly 780,000 people actually living in Cotonou, experiencing this moment not from afar, but from within the city itself?

Perceptions and Uncertainty in Cotonou

A month later, I have the opportunity to ask some people about that day. I have arrived in Cotonou, where I will be staying for a couple weeks to conduct some orienting interviews before continuing my journey to Parakou. While the city is chaotic, with the characteristic Zémidjans (motorbike taxis) constantly engulfing the streets with the sound of claxons and the smell of exhaust fumes, it also seems peaceful. It has been approximately six weeks since the coup attempts, and it is hard to imagine that these streets were once filled with gunfire and the sky with military jets.

During my interviews, I ask young Beninese about how they experienced the morning of the coup the attempt. James (pseudonym) (27), recalls: “First, I heard about the coup on TikTok. I was scrolling and I saw a video. In my head, I thought, ‘This is not Benin.’” Like many others, he first received the news about the coup attempt on social media feeds. “There was so much misinformation. A lot of people lied, some even said the president had been killed!”. Another interviewee, Fayola (pseudonym) (23), describes the witnessing of those different narratives on Facebook: “Some people said it failed, while others said it didn’t. It was not clear… We needed to know if we could go out or not. Only when we saw that the president was going to speak on TV did we understand that everything was okay.”

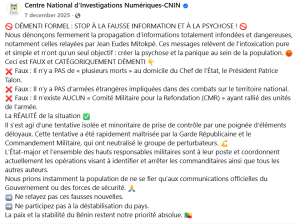

I also spoke to Maurice Tanthan, an expert on Beninese social media and disinformation. During our interview, he goes even further about the role of social media on that fateful day: “”In the case of the coup attempt, the spread of fake news was, in my view as a specialist, almost part of the coup itself. When information is not immediately controlled by official authorities, people can say anything online.” He explains how social media can be ‘weaponized’, and how the distribution of false narratives can help to destabilize a government. These narratives, he argues, can obscure clarity and create confusion, a strategy employed not solely by Beninese actors: “Much of this content actually came from neighbouring countries, such as Niger or Burkina Faso, from actors who wanted to destabilize the regime in Cotonou.”

The Fog of Social Media

The events of 7 December 2025 were experienced in a similar way by young Beninese as those watching from afar. Overwhelmed by the sudden news, we all turned to social media to make sense of what was occurring, hoping for some clarity. But instead of clarity, the social media feeds caused confusion, anxiety and disorientation. Information on social media moves fast, way faster than traditional media outlets, and its horizontal information flows allow for a space where information is produced and consumed at simultaneously. On that morning, the constant flow of conflicting narratives, rumours and disinformation created uncertainty not because information was absent, but because it was abundant.

This dynamic reflects what Stupart & Ahmed (2025) describe as ‘Mediatization of Conflict’. Social media did not simply report on the attempt, but its discourse actively shaped how it was perceived. Different narratives circulated simultaneously, as posts, videos and truths moved faster than verification could keep up. Among young Beninese, this resulted in feelings of confusion and uncertainty, generating a “fog of social media”, similar to the military term of a “fog of war”, where clarity is lost due to rapidly unfolding events. This ‘fog of social media’ did not only obscure the events of the coup, they resulted in a reshaping of how the political crisis was perceived. In a landscape where everyone can post, comment and share, new truths are constantly emerging and evolving.

And while the streets of Cotonou may seem calm, the memory of the coup attempt continues to live on through Beninese social media. Although it is now clear was occurred on that day, people continue to share their perspectives and debate what happened, shaping how others understand those events. It serves as a powerful reminder of the role of social media in times of political crisis. Social media platforms are far from neutral, but are active spaces where truths are circulated, contested and transformed.

Bibliography:

Stupart, R. & Ahmed, H. (2025): The Mediatization of Conflict: Critical Reflections on Center-Periphery Constructions in the Media. The Rowman & Littlefield Handbook of Peace and Conflict Studies