Authors: Luca Bruls, Mirjam de Bruijn and Bruno Allahissem

Authors: Luca Bruls, Mirjam de Bruijn and Bruno Allahissem

In the sand we see footprints of elephants. Seydou, a herder with a cheeky smile who relays a level of social cleverness that makes him an excellent herder representative, points at pieces of dried out faeces dispersed over the terrain. In la brousse, people observe unknown, previously unseen traces with great attention. In the far north corner of Mayo Kebbi West in Chad in a town called Binder, elephant traces have, over the past two years, become a major topic of conversation. If you would follow these round-holed prints across the land, a line would draw up from ancient corn fields, to mango trees and acacias, to grass, to water. The same points are frequented by nomads who keep livestock and by farmers to cultivate their land. La brousse in Binder is a crossroads of newcomers and natives who seek to pick the bitter fruits of these dry zones at a high price.

Arrival of a royal invasion

During a three-day research trip, we, Bruno, Luca, and Mirjam, exchanged with sedentarized herders, national parc employees, nomads, and governors to witness the turbulent nature and conflict of interests of the small town Binder. To arrive there, we moved about 150 kilometers West from Pala, the capital city of Mayo Kebbi-Ouest, a province close to the border with Cameroun. Binder is the fief of a Fulani kingdom that belongs to Adamawa, the 19th century Fulani empire covering a large part of Cameroun, Nigeria, also called Yola. The Fulani arrived in this area carrying the flag of Sokoto and Yola, to conquer the region for Islam. Since the end of the 18th century, they have ruled the area and demarcated the frontiers, by war. The region then must have contained rich bush, with large trees, rich grass, and enough water to keep cattle and horses and to grow the millet people needed. Wild animals must have been grazing along cattle herds and horses. The Fulani overruled the sedentary populations, who did not let themselves get conquered easily. The Moundang, ruled by their Gong, were warriors with magic power. One Moundang kingdom, Léré, was given autonomy, but only if the Gong would Islamize. Religious lines were starting to shape the use of the land, the demarcation of routes, and interactions. These kingdoms drew new lines in the landscape through their warfare and religious fanatism.

Binder territory became a space for nomadic pastoralism. The elites left their animals with herders in the bush. Other herders’ families subsequently came to this rich grazing area under the protection of Binder. In 1900 the Germans colonized Binder, and in 1918, after World War I the town became part of France’s colonization. Binder also became a corridor for transhumance from Lake Chad to southern areas. The colonial era allowed life to continue in Binder. Post-colonial partition brought Binder into Chad, hence it got separated from its brother and sister kingdoms, which Yola controlled. The Chadian border with Cameroun was a new line in the landscape that would have deep consequences for Binder’s future.

Our imagination of Binder was fed by the rich history of conquering. But the expected wealth and beauty are no longer there. We entered a small town with crumbling houses, with the hotel de ville in ruins, the ceiling in disarray, and walls that need urgently to be painted. At the central place of the small town, the Chadian flag dances in the wind on a roundabout opposite the palace. The two landmarks date from colonial times built by the French on the foundations of the Germans. Both wear the marks of passing time, and as we discovered, for 20 years they have not renovated this place. The vestibule is ornamented with a few old photos that are falling from the wall. We waited for the Laamido, the paramount chief of Binder, to receive us. He was taking his bath.

An old man, who carries symbols of royal slavery led us to the central place in front of the palace. We filled the waiting time with a discussion with the notables who came to accompany the Laamido. They are proud of the rich history of Binder, which belongs only to their memories.

Confronted with newcomers

The GS (General Secretary) of the town hall Saadjo received us in the hotel de ville. His radiant eyes showed high energy, and a wish to make change happen. The radiance covers despair, as we soon discovered. He feels abandoned in this frontier town Binder. The Chadian state is not supportive. The money for the renovation of the hotel de ville has not been released, for how many years now? Binder has no judge, instead, the judicial police occupy part of the hotel de ville, and they make a lot of noise, which hampers his work. He shows the document that tells the story of Binder, written by Eldridge Mohammadou, a late Cameroonian historian. He is the son of one of the defunct kings of Binder and cousin of the Laamido. He is a prince. The first story he shared is about the elephants. Their space is protected. The fact that they eat their millet and maize in the fields makes life impossible in Binder: ‘we will suffer hunger’. He followed up with the story of the imposition of the parc. He was drawn into the project to turn the reserve de faune which was established in 1974 into a national parc with status 1. This means that no one, except les blancs, can enter the park. The project was led by French. He released his thoughts that there might be more in the park, in the sous-sol. Why are they denied access? He was part of the negotiations and confronted with the little room for manoeuvre that was left for them. He decided to leave the organization. ‘I was also part of it and helped them draw the lines,’ Saadjo said with a regretful voice. He might decide to leave Binder, to his beloved Addis Abeba? In the meantime, he has decided to work with women in the village, to plant trees, make compost, and reintroduce the old practices of weaving. The beauty of his culture.

Shrinking of pastoral space

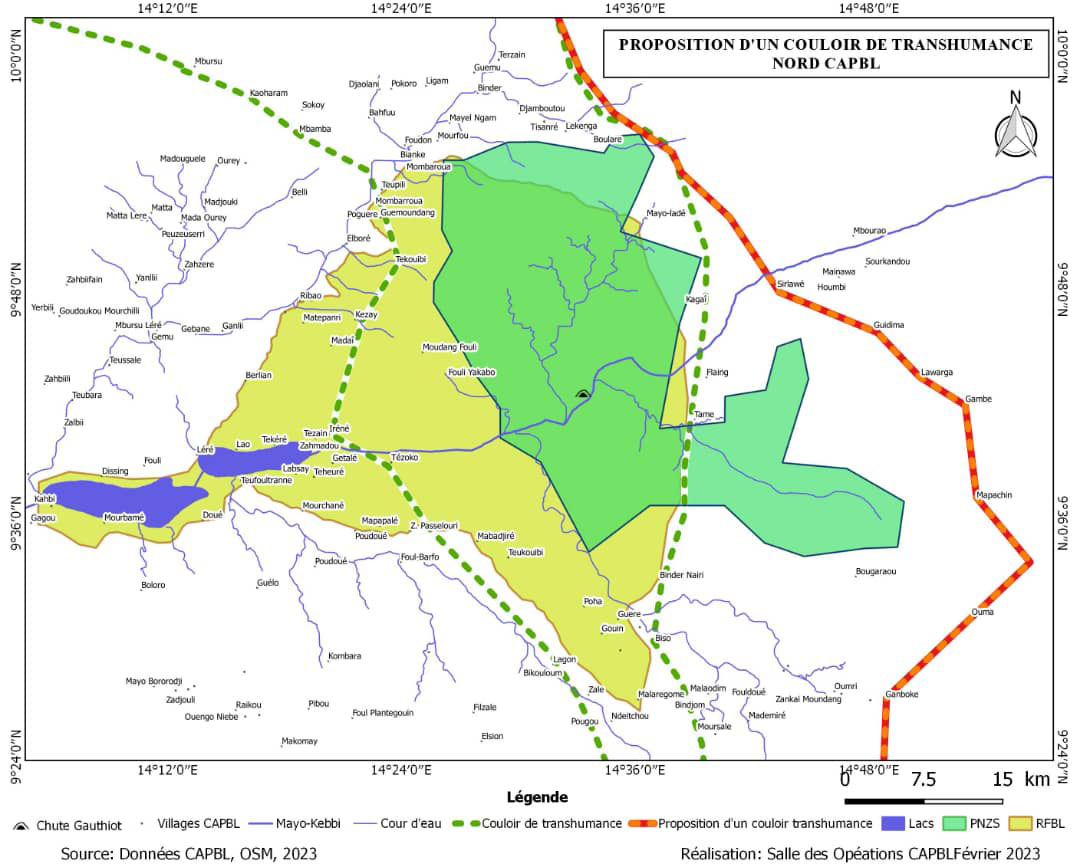

In a guarded office, with three jeeps lined up in a well-cared-for courtyard, we met with the director and assistant programmer of the parc, known under the French institution Noé. Attached to the wall was a designed map of the area, demarcating a green, yellow, and white zone. The green zone, defined in 2022, is owned by the parc in collaboration with the state and is prohibited to enter except for their personnel. The yellow zone indicates a partial living zone and fauna reserve established in 1974. The white zone indicates areas beyond the direct influence of the parc. The red line marks the proposed new transhumance route.

At a long table, we settle to listen to an obfuscating narrative about the parc’s objectives: protecting the rare ecology, and wild animals, boosting ecotourism, and developing new corridors for transhumance. Since the arrival of the parc, however, conflicts have troubled the quick implementation of their plans. Nomads do not agree to give up the greener pasture areas and due to the mobility of their profession, they are not used to following cartographic lines. This context has resulted in a battle of hide-and-seek between the nomads, carrying arcs, and the parc’s guards who, loaded with weaponry, wave around with fines of up 10.000 FCFA per cow for Chadians and even higher prices for those from Nigeria, Niger, and Cameroun. The installation of surveillance cameras sustains this punitive system. And money disappears in the pockets of the state, the parc, and collaborators in Binder’s community.

Amidst the parc’s objective to protect nature, we sensed a militarization of nomads’ livelihood strategies and an abstaining from the local community’s efforts and wishes to search for shared solutions. The assistant programmer pointed at an unpublished map, to show the two historical transhumance routes that cross directly through the green and yellow zone. Therefore, the parc’s employees suggested to develop a new transhumance corridor outside of the parc. It remains undiscussed what will come of the farmers, herders, and villagers who happen to live along this imagined, soon-to-be-actualized line.

Leftover lands

However, la brousse does not adapt to human-drawn lines. It is an undefinable free space where animals search the best of green and where luck and misfortune can cross a traversers’ path. Like Seydou said when we visited the borders of the state-protected Parcs de Noé: “La brousse attaque.” (The brousse attacks.) As he sees his plantations of corn, haricots, and berebere eaten up by elephants and his horned cows and goats barely surviving on the leftover lands between the parc and Binder, he no longer feels safe in what used to be his home. He and other inhabitants of Binder feel closed in between the 15 km close border of Cameroun on the west and the 3 km close border of the parc on the east. They have no way to go and cannot count on the support of the government. Guards and French NGO workers now decide where Binders’ folks can herd their animals. Meanwhile, the growing number of big troops of cattle owned by rich elites with little herding experience and a capitalist mindset escape the harsh measures.

Is the only solution sedentarization as proposed by the adjoint maire and president of the association des éleveurs in Pala? Will the people from Binder and its surrounding areas adapt to ecotourism and the course outlined by the NGOs? Who will redefine the frontiers of Binder is yet to be seen. Meanwhile, transhumance continues in the eye of the tiger.