On my final day in Lausanne I made a visit to le Collection de l’Art Brut, where lush crafts of ‘outsider art’ fill up the three storied building. A Bordeaux red display sign reads: “Art Brut is made by self-taught people who often live on the margins of society, either as rebellious souls or as beings who are impervious to normative and collective values. Among them are loners, outcasts, resident from psychiatric hospitals, inmates, seniors, and whose creative expression exists for itself, without any concern for public criticism or what other people might think.”

Wandering through the dim lighted halls of the museum, I read the stories of the artists whom all, in one way or another, challenged the status quo. As non-conformists, as untrained practitioners, as anomalies they make everything usual become alive. They intrigue and promise a charm of what life on the fringe entails. They seem to scream “no!” to a textbook path of life.

See: Photo: Hans Krüsi, untitled, © photo credit Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

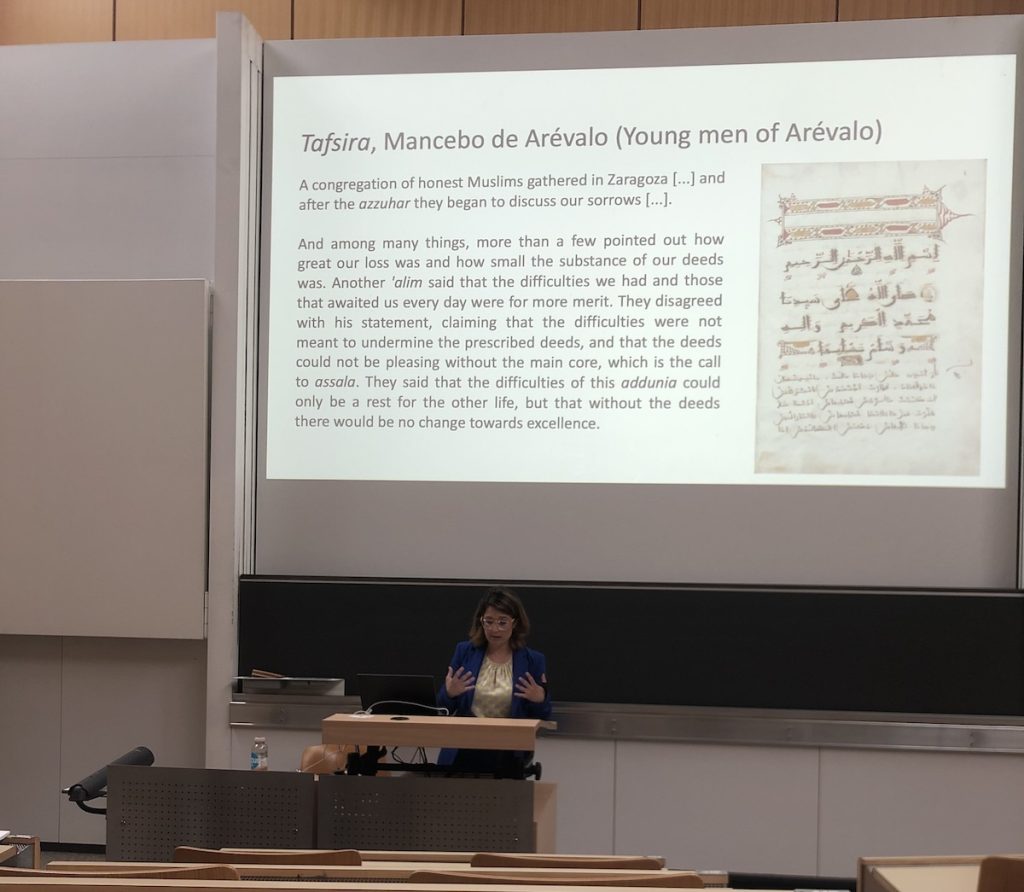

While looking at the paintings and sculptures of the artists, I cannot but think of the stories about the Mudéjar and Muresco. They were Muslims who lived in the Iberian Peninsula during the Christian reconquest and developed an architectural and artistic repertoire from the 10th until the 15th century . I learned about this group during a keynote by Mónica Colominas Apericio at the ENIS Spring School, which I attended from June fourth until June seventh at Lausanne University. In a collective endeavor, PhD candidates, master students, and professors sought to unpack ‘the peripheral’ in relation to their work on Islam and with Muslims on the geographical, normative, political and religious margins. The Mudéjar and Muresco were quote-on-quote peripheral, as they lived on the geographical and religious borders of a Christian-run land. These Muslims related to what happened in non-Muslim centers. They coped with the hardships of the time and negotiated their positions in a predominately Christian environment. Therewith, like artists of the Art Brut genre, the Mudéjar and Muresco redefined the territorial, material, and cultural boundaries of expression.

Photo: Story of the hardships of the Muresco

What happens in the periphery is not simply free-spirited or untamed. It is a response to the contact with others and centers of legitimization and authority. As such, the presentations of my peers made clear that the mainstream or popular and what falls out of it are always a product of contestation and a battleground for discussion. It is in the contact zone that Muslims designate differing practices as heterodox or heresy and that “alternative authorities” emerge, says keynote speaker Thijl Sunier.

In my presentation, I elaborated on the spatial and relational dimension to demonstrate how a Muslim community in Chad creates spiritual environments. Mobility is essential in this context and runs counter the dichotomy of the center and periphery. I discussed khalwāt (schools for Quranic learning, dhikr, and care) as places where women from Chadian villages, young Fulani boys from Lac Chad, Niger, and Cameroon, and displaced families from Nigeria meet to practice faith. During exchanges in these Muslim spaces in N’Djaména a multiplicity of voices, events, and tracks come together. The khalwa is a meeting point of nomad and non-nomad routes, as people stay, come and go. It is a place, often on the outskirts of the city or in villages, inhabited by people from different insecure and Muslim epicenters. The khalwa thus encapsulates both centrality and periphery. Due to its mobile character the khalwa is a zone to rethink the peripheral. More, counter to the idea that my research is worthy of the stamp periphery from the perspective of Islamic studies, for the community in N’Djaména, this place is far from peripheral, instead it is central to their religious quests and everyday life.

What are the margins of society is debatable – be it from a scholarly-, state and border-, material, or cultural perspective. This discussion, as Sara Bolghiran also pointed out in her presentation, has long been on the agenda in subaltern studies and colonial critiques by the works of Gayatri Spivak (1988). As I have left Lausanne and continue my grasp of the peripheral and margin, the Art Brut connoisseurs have taught me one thing: that the margin is a site of creativity, as well as “a site of resistance – as location of radical openness and possibility (hooks 1989, 23)”. The margin holds a promise.

Sources

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. 1988 [2010]. “Can the Subaltern Speak? Can the subaltern Speak?” In Reflections on the History of an Idea, ed Rosalin Morris, 21-78.

hooks, bell. 1989. “Choosing the Margin as a Space of Radical Openness.” Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media, no. 36, 15–23.