On Thursday November 20 and Friday November 21 we, the Nomade Sahel team, had the pleasure to host a group of fantastic academics at Leiden University for a first workshop: The Power of Social Media Networks: scientific research on the entanglement of online and offline networks in times of conflict in Africa. The workshop allowed us to present our research findings up to this point. Foremost, we collaboratively reflected on core questions in relation to research on conflict, networks, digitalization, archiving, and computational methods with a focus on sub-Saharan Africa. We ate an unnecessary amount of sandwiches and pepernoten while all present defended their perspective on how social media shape war and conflict dynamics? And under what conditions do the interaction and entanglement of digital and physical social networks contribute to the intensification and violence of conflict?

On day 1 Luca Bruls opened the workshop and explained the project’s approach to networks as a place that implies agency, decision making and strategy. Departing from a tradition of anthropologists who have looked at networks as social practice, meaning: “the microscopic moment a person connects with another to constellations of relationships between individuals and organisations emerging from their self-ascription of, and emplacement within networks across states, regions continents and even oceans (Cañás Bottos et al., 2024, 7).” The workshop is placed in a post-digital approach to research. Seeing the online and offline as entangled; and embracing the messiness and unpredictability of the postdigital world; the postdigital means “a condition where the virtual and physical mediate each other to form hybrid spaces that transcend the online/offline distinction.’ (Wang and Canagarajah, 2024)” Here digital and non-digital are inseperable.

In the following hours, researchers presented how their work on entangled networks based on kinship, friendship, work, nationality, religion, and community facilitate people with information, financial support, safety, care, and trust. The discussion of online groups on Reddit, Facebook, WhatsApp, and TikTok indicated how concentrated online spaces are like a microcosmos of what happens at a larger scale in the Sahel.

Filtering information

“Conflicts are always there, but they magnify and accelerate through social media.” – Lidewyde Berckmoes

Mirjam de Bruijn and Jelena Prokic layed out research that Nomade Sahel has been conducting on Facebook usage among Fulani and visualized the media ecosystem among elites, youth, pastoralists, and family. In their search for entangled networks, they propose the advancement of ‘computational ethnography’. Computational ethnography is a mix of quantitative and qualitative methods, to grasp large scale behavioural patterns through computational techniques like NLP, and make sense of them through an ethnographic approach of interpretation, meaning-making, and contextualization.

Corinna Jentzsch used examples from her research on conflict in Mozambique to discuss how armed groups, civilians, and state actors respond to limited information access during emerging insurgencies. In insurgent context, where in the early phases there often is confusion and a lack of knowledge about violent actors, the digital spaces are important environments for exchange and organization around information. The risky and precarious work of community journalists and local networks of support who distributed information on Facebook, WhatsApp, and radio is especially important in Mozambique. From Corinna’s presentation participants addressed the adoption of media by the state, as well as their role in violence towards journalists. Others addressed the intensification of social media networks due to its growing speed and scale and the consequent blurring popular participation of ordinary people in the exhabiration of violence.

Material circumstances

“From the smartphone perspective Africa is already the future!” – Geert Lovink

The number of smartphones grows in the Sahel, and that implicates a growing market for China, as well as for American social media platforms. Everyone confirmed this from their unique fieldsites. Jethrow Norman pointed at the hig connectivity he experienced during research in Somaliland and how conflicts are currently livestreamed. In Northern Somalia kinship is central in how people use online and offline infrastructures in search for political sovereignity. ‘Platform kinship’ enables a nested structure of clans based in the diaspora and the region to raise money, grow businesses, and build military trust for life-and-death coordination.

While in the case of Jethrow, clans gained certitude, land, and business through the renewed digital infrastructures, Silvie Ayimpam lay bare a similar infrastructure of credibility for state actors in Burkina Faso. She directed our attention to the online image war directed by Ibrahim Traoré, wherein images shape public truth and legitimize armed conflict. Therewith she explained how the physical intensification of jihadist and state conflict and the incertitudes that come with this, can contribute to patriotism and post-truth online. In reflection of Reddit posts about Ibrahim Traoré, the president of Burkina Faso, she disected glorifying and critical conversations about him.

“‘Panafricanists’ refind themselves on the net, they were orphans and they found a new leader.” – Sylvie Ayimpam

Lidewyde Berckmoes addressed another aspect of materiality that is prominent in the discussion on digitalization and conflict in sub-Saharan Africa: digital disconnections. Many researchers present recognized issues contributing to disconnections, like isolazation, impoverishment, media shut-downs and a disfunctional organization. In Burundi, however, Lidewyde pointed at ‘deliberate’ forms of disconnection, when during and after 2015, youth, civil society and political opponents increasingly began organizing themselves through social media. In the diaspora connections shifted or dissolved due to flight, overwhelming emotions and expectations, and death. Disconnections were a form of protection and raised the question: who wants to belong?

New Extractivism

During a final lecture, Geert Lovink moved away from Africa and fed the participants with a critical discussion of Internet studies and the various traditions of network research. The differentiation between media, network, and platform showed that with the rise in rightwing populism, Brext, Trump, and capitalism, the network disappeared and degenerated into the platform. Lovink played a terrifying video visualizing a panopticum of the platform logics wherein social media are a fundamental driver of data extractivism and digital colonialism. All users are exploited in this dynamic. The dark sides of the Internet showed how platforms are inherently designed in a violent and brutal way, such that it impacts war and everyday social realities. Can we hence draw the conclusion that no matter what social media platforms are inherently violent?

Deletion and preservation

There is a problem that scientists have: we have collected our own data and we cannot put it in someone else’s machine, like of Microsoft. For us in humanities who work with sensitive data: that is even more the case. We have to guarantee our privacy. We need data containers that are very protected: we cannot throw it into a factory, because you loose anonymity. – Mirjam van Reisen

On the second day of the workshop, Michael Innes presented his experience with forensic research, archiving, and the preservation of documents and evidence of violence. Based on case studies of document collection in conflict zones in Afghanistan and Iraq, he addressed the difficulties with national and private institutions that arise from collecting, digitizing, and archiving multimedia materials.

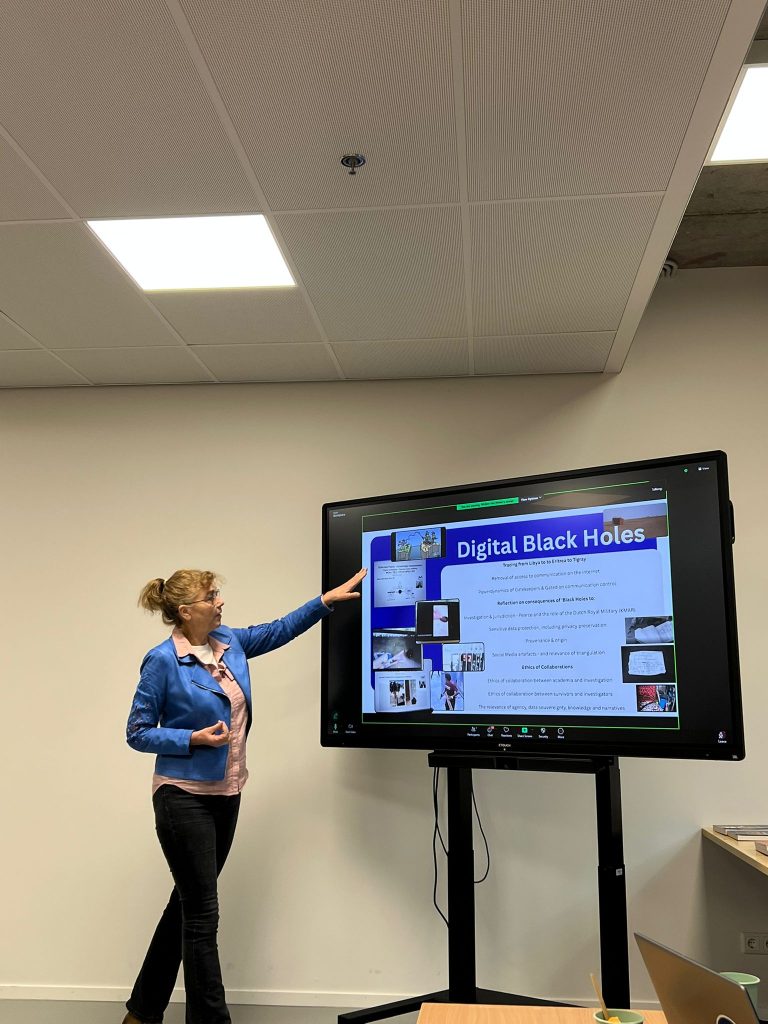

Mirjam van Reisen continued the discussion in reflection of the ethics of preservation of sensitive data. Her case study was a collaborative investigation with the Dutch Public Prosecutations Department (Openbaar Ministerie) on networks of human trafficking from Eastern Africa to Europe. She described digital ‘black holes’ to refer to the temporary removal of digital communication on route, in a similar fashion to what Lidewyde Berckmoes referred to as digital discommunication. Social media video’s turned out to be an important evidence in court. Due to the high sensitivity of the data that was used as evidence in criminal court, the project upheald strict FAIR data principles of data souvereignity and agency.