This blog is written by Said Aboubakkar and Luca Bruls. It is the result of the participation in the project ‘Support for the drafting of reports on nomadic pastoralism by GIZ and Voice4Thought (V4T)’, whom co-jointly organized a workshop in N’Djaména in 2025.

كتب هذا المدونة سعيد أبو بكر ولوكا برولز. وهي نتيجة المشاركة في مشروع ”دعم صياغة تقارير عن الرعي البدوي“، اللذين نظموا معاً ورشة عمل في نجامينا في عام 2025.

For English and French, see below

Pour l’anglais et le français, voir ci-dessous

ارتفاع وانخفاض للقرية العجيبة

“ججل أمين رجرول ها دربالي, مناني هوبر ديام ورتي ها سلسيل… في آخر مرة ذهبنا إلى دوربالي، سمعنا نبأ ظهور المياه الجوفية في سيلسيل.” قول بنت الشيخ. وهي تنتمي إلى عشيرة ماري فولاني، وهي الابنة الوحيدة للشيخ محمد أزراق، مما أكسبها لقب بنت الشيخ. وهي تروي القصة بفخر. عندما تبتسم بشفتيها الداكنتين المغلقتين، لا يزال بإمكانك أن تشعر بشرورها الشابة. تواصل بنت الشيخ: ”قالوا [سكان دوربالي]: “ارتفعت المياه على الأرض التي كان يعيش فيها والدك الشيخ محمد أزراق”. عندما سمعنا الخبر، طلبنا من سائقنا أن يأخذنا إلى سيلسيل، حتى نتمكن من رؤية مياه والدنا. توقف هناك راعي يحمل عصا في يده، وضرب الأرض، فاندفعت المياه. بعد ذلك، بدأ الناس يذهبون إلى الينابيع، يحملون المياه ويشربونها ويغسلون وجوههم بها. وكان بينهم أعمى، ففتح عينيه عندما غسل وجهه. وكان بينهم مرضى، فشفاهم شربهم المياه فجأة. وكان بينهم مشلولون، فاستطاعوا الحركة بعد شربهم المياه واستحمامهم بها. قال الناس في دوربالي: ”شربنا منه واستفدنا منه.“

بنت الشيخ تروي القصة وهي جالسة في غرفتها المظلمة المزينة بستارة وردية لامعة وعشرات الملصقات لشيوخ تيجاني مشهورين من نيجيريا والسنغال والكاميرون. تقع الغرفة داخل الزاوية (أي مدرسة قرآنية ومسجد في آن واحد). قام والدها ببناء هذا المكان في قلب نجامينا عام 1973. كان الشيخ محمد أزراق زعيماً دينياً وعالماً ورعيّاً ومزارعاً له جذور في الكاميرون ونيجيريا. كان من أتباع العالم السنغالي الشيخ إبراهيم نياس وتلميذاً بارزاً للشيخ أحمد أبو الفاتح اليروي في نيجيريا الاتحادية. بدوره، كان الشيخ أحمد أبو الفتاح تلميذاً للشيخ إبراهيم نياس. كان الشيخ محمد أزراق لاعباً رئيسياً في نشر الطريقة التيجانية في تشاد. كان أحد تسعة شيوخ أرسل إليهم الشيخ أحمد أبو الفتاح رسالة يمنحهم فيها سلطة مطلقة على شؤون الطريقة الدينية في تشاد. توفي الشيخ محمد أزراق في عام 2001، لكنه ترك بصمة لا تمحى على مجتمع الفولاني والتيجاني الذي يعيش في شمال وشرق وجنوب وغرب نجامينا. تعرف المجتمعات من تشاد إلى الكاميرون ومن نيجيريا إلى السنغال بأعماله واسمه وتؤمن بالتدخل الخارق للطبيعة للشيخ في عالم البشر. مثل سكان دوربالي، الذين يتذوقون ويشعرون ويرون مياه البئر السحرية التي يُفترض أن لها خصائص علاجية. يعكس التفاعل الحسي نظرة مجتمع الفولاني إلى العالم بخشوع واستمرار الأهمية الدينية للشيخ. هناك ما هو أكثر من المعجزة. فهي تلفت الانتباه إلى موضوع الرغبة، المياه العلاجية، في مجتمع واجه مخاطر صحية ونقصًا في المياه منذ الخمسينيات على الأقل.

مؤلفا هذا المقال هما سعيد أبوبكر ولوكا برولس، اللذان التقيا حول الزاوية في الشوارع الضيقة في العاصمة التشادية نجامينا. التقينا في الزاوية في شوارع ريدينا الضيقة، وهي حي في العاصمة التشادية نجامينا. في إحدى الليالي المتأخرة أثناء سيرنا إلى الحافلة، أعرب سعيد عن رغبته في كتابة قصة حياة الشيخ، فخطرت لنا فكرة التعاون. بعد فترة وجيزة، بدأنا البحث عما تبين أنه أكثر بكثير من مجرد سيرة رجل ذي مؤهلات إسلامية. فقد كشف البحث عن قصة مجموعة من البدو الفولانيين الذين تحولوا جزئيًا إلى حياة حضرية واستقروا في أماكن ثابتة. وبسبب ظروف المعيشة الجديدة، فضلاً عن الفقر الذي واجهوه، قاموا بتكييف تنظيمهم الاجتماعي وسعوا إلى تحقيق الاستقرار المالي من خلال الزراعة وما توفره نجامينا. كان الشباب يتاجرون في السوق، بينما كانت النساء يبعن الطعام والأشياء من حين لآخر داخل المنازل. لعب الشيخ المطلع دوراً قوياً في هذه التغييرات. كلما سافر أكثر للحصول على المعرفة الإسلامية وكلما بنى المزيد من مدارس القرآن، أصبح رجلاً ذا شبكة اجتماعية واسعة وسلطة كبيرة في مجتمعه. تبعه أفراد عائلته في رحلاته واستفادوا من توجيهاته ليصبحوا قادة روحيين بأنفسهم. جاء أبناء القساوسة للدراسة في المدينة، وغالبًا ما تركوا ماشيتهم المستقبلية وراءهم. تظهر سيرة الشيخ والتجارب التي رواها أفراد عائلته أهمية الإسلام في مجموعة بدوية تتكيف مع أنماط حياة أخرى.

قمنا بجولة في المناطق الحضرية في نجامينا، وترددنا على الأحياء المختلفة حيث استقر مزيج من سكان المدينة الأصليين والرعاة السابقين وحفظوا أحداث القرن العشرين. توجهنا إلى حاجر لاميس، حيث غطت الأمطار الحقول باللون الأخضر، واستقبلنا المزارعون والعائلات التي لم يتبق لها سوى القليل من قطعان الأبقار الحمراء في منازلهم المبنية من الطوب الطحلب. عبرنا النهر في شاري باغيرمي، حيث تظهر الحقول الممتدة بقايا الذرة والقمح التي زرعها مزارعو الفولاني. وكأنهن يجمعن الحبوب الذهبية من بين الرمال، روت نساء مثل بنت الشيخ وزهرة ورجال مثل خليفة (توفي عام 2025) وموديبو، الذين التقينا بهم لاحقًا، ذكرياتهم الحية. نادرًا ما توقفوا عن ذكر اسم المكان سيلسيل. للوصول إلى هناك، اتجه الشيخ محمد أزراق نحو الشرق…

الهجرة التي جلبت الشهرة

بدأت رحلة الشيخ في والوجي، الكاميرون الحالية، حيث ولد وترعرع ووضع أهدافه. هاجر الفولانيون لقرون، بحثًا عن البيئة المناسبة لمواشيهم وأحيانًا لأسباب أمنية، كما هو الحال مع عائلة الشيخ محمد أزراق. أولاً، دخلت هذه العائلة البدوية تشاد لأن السلطات في الكاميرون ضغطت عليهم لدفع ضرائب على مواشيهم. ثانياً، كانوا يبحثون عن الأمان من السرقة والقتل. وفقاً لرواية أحد خدم الشيخ، ساينا، قتلت مجموعة من ”الفرنسيين السود من أصل سنغالي“ شقيق الشيخ في أحد الأيام. تركنا هذا التعليق نتساءل عن التفاعلات التي قد تكون سبقت هذا الصراع بين الراعي والإدارة الاستعمارية. حدث ترك الكثيرين في حالة من القلق. دفعت هذه الظروف الشيخ وعائلته إلى التفكير في مغادرة الأراضي المستعمرة. عندما سمع الشيخ وبعض إخوته بأخبار الأراضي المحيطة بدوربالي في تشاد، لم يترددوا في مغادرة والوجي. كان العديد من الإخوة وأبقارهم قد هاجروا بالفعل إلى دوربالي حوالي عام 1947 وأبلغوا إخوة الشيخ بالظروف الأفضل في دوربالي، حيث لم يواجهوا السرقة والضرائب وسفك الدماء البريئة، كما تشير قصة ساينا.

في صباح أحد أيام أكتوبر، دخلنا الزاوية في نجامينا لإجراء مقابلة مع خليفة، ابن عم الشيخ محمد أزراق. نجد مجموعة كبيرة من المهاجرين، بعضهم يغسلون ويكتبون لوحاتهم (لوحات)، والبعض الآخر يغسلون ملابسهم. يجلس سيدهم أمامهم ويؤدي دوره التعليمي. عندما ندخل صالون الشيخ، نجد خليفة ويدعونا إلى غرفة الشيخ الراحل محمد أزراق نفسه. الغرفة مليئة بالصور التذكارية للشيوخ الذين كانوا يزورون الشيخ محمد أزراق، بما في ذلك صور الشيخ النيجيري أبو الفاتح وأبناء الشيخ إبراهيم نياس من السنغال. نجلس على سجادة، أمام خزانة مليئة بالأعمال العلمية الإسلامية. عندما يروي لنا خليفة قصة الرحلة التي قام بها أعمامه ووالده والمصاعب التي واجهوها خلال المسيرة، يبدو أنه متأثر. ترتفع نبرة صوته وتنخفض، خاصة عندما يقول له سعيد: ”لا أصدق أنك تغلبت على كل هذا“، فيرد خليفة: ’كاي‘ ويهز رأسه يمينًا ويسارًا، نتيجة لانفعاله. يواصل خليفة: “كانت هجرة صعبة للغاية واجهنا فيها مصاعب. كانت المسافة من والوجي إلى دوربالي طويلة، والشمس حارقة لدرجة أن التربة تحت أقدامنا كانت تشعر وكأنها جمر، لأننا كنا نقطع هذه المسافة سيرًا على الأقدام خلف الماشية”.

عندما أنهى الشيخ دراسته، انضم إليهم. وجدهم في ديرباجي، وهي قرية قريبة من دوربالي. هناك، بدأ بتعليم القرآن الكريم للفتيان والفتيات. نظرًا لتأثير الدين الكبير على قبيلة ماري فولاني، سلمت الجماعة شؤونها إلى هذا الرجل المليء بالحكمة الإسلامية. ترتبط أهمية الدين في الجماعة جزئيًا بالدور الذي يعتقد أفرادها من قبيلة فولاني أنهم لعبوه في نشر الإسلام في جميع أنحاء إفريقيا. في المقام الأول، وثقت العائلة في الصفات الدينية والروحية للشيخ محمد أزراق. كان من لحمهم ودمهم، لذا منحوه القيادة.

منذ ذلك الحين، لعب الشيخ دورًا في تحركات وسفريات قبيلة ماري فولاني. لم يقتصر الأمر على طاعة الناس له لأنهم اعتبروا مخالفة الشيخ مخالفة للشريعة. كان هو وإخوته يمتلكون أيضًا عددًا كبيرًا من الماشية، وهو عامل مهم في التنظيم الجغرافي للفولاني. في عام 1952، انتقل الشيخ وأقاربه إلى غاويل، وهي منطقة تبعد خمسين كيلومترًا عن ديرباجي. كانت الأرض هناك غنية بالعشب والبرك، وبالتالي كانت مكانًا أفضل للأبقار التي يربونها. في غاويل، افتتح الشيخ أول خلوة له، حيث كان يعلم فيها أطفال إخوته وأقاربه فقط. بعد بضع سنوات فقط، سنحت فرصة جديدة للهجرة إلى سيلسيل في عام 1957، فانتقل الشيخ محمد أزراق وبعض أقاربه، بينما بقي الآخرون وواصلوا إدارة الخلوة.

البئر وفيرة

من المحادثات مع بنت الشيخ وخليفة حول السنوات التي قضاها الشيخ وأقاربه في سيلسيل من عام 1957 إلى عام 1978، اتضح أن الحياة الاجتماعية في سيلسيل ظلت تتسم بالتنقل. كان الناس والماشية يتبعون نزوات الموسم لتأمين قوتهم. عندما تساقطت قطرات المطر الأولى في الخريف، عاد الماعر من جميع أنحاء البلاد إلى تربة سيلسيل. قام الرعاة ذوو العمامات الذين استقروا في قرى مثل هديدي حول بحيرة تشاد بضرب عصاهم على مؤخرات أبقارهم، مقتربين منها شبرًا شبرًا. المهاجرون التابعون للشيخ محمد أزراق، وطلابه الأكبر سنًا وزوجاتهم في نجامينا، وضعوا القليل من ممتلكاتهم في حقائبهم وغادروا إلى القرية المتواضعة، متمنين لحظة خصبة. في هذه القرية، كان الرعاة وسكان المدن والمزارعون من المااري الفولاني يجتمعون كل عام عندما تصبح التربة رطبة. الماء عنصر أساسي في الحياة، وبالمثل فهو محرك للتواصل. إنه يجمع الناس معًا.

في شرفة صغيرة ذات سقف من القش في قرية ميبي على ضفاف نهر شاري، نلتقي بموديبو. موديبو يبلغ من العمر 77 عامًا وولد بالقرب من بحيرة تشاد. بعد أن درس القرآن مع الشيخ محمات أزاراق في نجامينا، قرر أنه يريد أن يعمل في الزراعة وانتقل إلى سيلسيل، حيث أقام طوال العام. لا يندم على الأيام التي قضاها في القرية، لكنه يروي بقلب حزين كيف انهارت القرية ببطء. في سيلسيل، كان الناس يعيشون بالقرب من بئر بير تورني موسى ناين، على أرض فولاني يدعى بيسكي. للحصول على الماء من البئر، كانوا يمشون مع حميرهم لمدة ساعة. كان البئر مملوكًا للعرب الذين يربون الأبقار، في عهد السلطان أحمد جوجال. كان العرب يعيشون في قرية أخرى ويأتون كثيرًا لتحية جيرانهم الفولانيين. يروي موديبو: ”همما كولو جو في باكانا. ساباب شيخ أزراق دا.“ ويصف كيف كانوا مثل العائلة. ”كان ذلك بسبب المحبة والدين.“ لم يقتصر الفضول تجاه الشيخ على الفولاني الماري فحسب، بل امتد إلى مجتمعات عرقية أخرى. خلال مقابلة في ماني كوسام، وهي قرية في حاجر لاميس، أضاف حسيني أن الشيخ كان لديه طلاب عرب ومسا في سيلسيل. حسيني هو رجل يبلغ من العمر 85 عامًا يرتدي نظارات ضخمة ويتمتع بجاذبية كبيرة، قضى طفولته مع الشيخ في غاويل كراعي. يثني حسيني على الشيخ ويتذكر رائحته الرائعة التي تشبه رائحة خشب الصندل. استمعنا إلى صوته الخشن وسط أصوات ماعزه التي تثغو في ماني كوسام. كان يحب هذا الرجل ولا يزال يحبه: “كان الشيخ فقيرًا. لكن كبار السن أحبوا الرجل، لأنه كان موديبو (عالم دين) يعرف القراءة”. على الرغم من فقره، اكتسب الشيخ مكانة لنفسه ومجتمعه.

فرض الشيخ الإسلام بلا شك أينما استقر. عندما وصل الشيخ وزوجتاه إلى سيلسيل، قام بتعليم أطفال إخوته وأخواته حول المدفأة، وهي عادة حافظ عليها أحفاد الشيخ في ميبي. تولى أحد طلابه الأوائل، الذي يعيش مثل موديبو في ميبي، مسؤولية الدروس في سيلسيل عندما غادر الشيخ إلى نجامينا في أواخر الخمسينيات. أصبح الشيخ أكثر اندماجًا في المناطق الحضرية في نجامينا. على الرغم من أن الحياة لم تكن سهلة في الأحياء الفقيرة في وسط نجامينا، إلا أنه تمكن من العيش مع ازدياد أتباعه من المسلمين. في غضون ذلك، استقر طلابه في سيلسيل وأصبحوا معلمين للقرآن. تغيرت مصادر دخلهم. كان موديبو و ثلاثة آخرين مسؤولين عن زراعة الحبوب وقراءة القرآن في الليل. ركزت زوجاتهم على معالجة الحبوب. خلال موسم الأمطار، استقبلوا أقاربهم من مربي الأبقار والمهاجرين من الشيخ من نجامينا. كان انتشار الإسلام بين الماري فولاني دافعًا لاعتماد أسلوب حياة زراعي. بسبب الطلب المتزايد على المحاصيل الغذائية في المدينة بسبب تزايد عدد الطلاب في الستينيات، تحول الماري فولاني إلى زراعة المحاصيل الغذائية لتلبية الطلب.

حتى يومنا هذا، تعيش زهرة على الجانب الآخر من طريق الزاوية. زهرة تبلغ من العمر 69 عامًا. يغطي لافاي زهرة رأسها بشكل فضفاض. تلامس يداها الطويلة النحيلة، التي تميز الرعاة الطويلات، ساقي لوكا وهي تعرض لنا وجهة نظرها حول الأنشطة الزراعية في سيلسيل. في عام 1968، استقرت زهرة، ابنة راعي، في نجامينا في سن الثانية عشرة بعد زواجها. في نفس العام، سافرت مع زوجها وزوجين آخرين ونصف المهاجرين الشيخ إلى سيلسيل. كل عام، خلال فترة خمس سنوات، كانت تقيم في سيلسيل لمدة ستة أشهر. تقول بصراحة إن الأيام لم تكن سهلة، فقد كانت تقوم مع نساء أخريات بـخدمة مور. كلماتها تنقلنا إلى عالم آخر: ” أمشي المي, يمشي خطب. نيدجو خالة بادينا, نسي عيش. دا شغل هانا أجور باس….” دافع إسلامي تردد صداه أيضاً في كلمات بنت الشيخ: “الزراعة فيها بركة.” ذهبت زهرة إلى سيلسيل لأن الشيخ طلب منها ذلك، وهي لم تكن لترفض طلباً منه، الذي تدعوه بحب والدها. لذلك، في أواخر الستينيات وأوائل السبعينيات، كانت نساء القرية يعدن الطعام، وزرع حوالي 300 طالب حبوب القمح والذرة والبامية، وحصدوا المحصول عندما تلمع السنابل تحت أشعة الشمس في منطقة الساحل. وبمجرد انتهاء موسم الأمطار الغزيرة، قاموا بتنظيف الأراضي، وأخذ رجل مسؤول نصف المحصول إلى نجامينا. هناك، قامت زوجات وأبناء عم الشيخ محمد أزراق بتخزين 30-40 كيسًا داخل الزاوية، مما كفى طلاب القرآن وعائلات معار في الزاوية من الطعام طوال العام تقريبًا.

الوداع: تغيير الاتجاه

لكن المخزون لم يدم طويلاً. ازداد التعب في سيلسيل. بعد أن غادرت زهرة سيلسيل، انتقلت خالتها، إحدى زوجات الشيخ، إلى سيلسيل لكنها توفيت بسبب مرض خطير أصيبت به من المياه. واجه من بقوا في القرية نقصًا متزايدًا في المياه من عام 1974 إلى عام 1978. لجأ الكثير من الناس إلى أكل الأوراق لتغطية جوعهم. قال موديبو في ميبي بوجه حزين: ”بير دا ويجيف باس، أكل ما في، المي ما في... وهذا ما أتى بنا إلى هنا“. توقف الرعاة عن القدوم بأبقارهم في موسم الأمطار. في بداية موسم الجفاف عام 1978، غادرت مجموعة الرجال والنساء والأطفال والأبقار المستقرة في سيلسيل إلى الأبد. بمجرد وصول الفولاني، غادروا سريعًا سيرًا على الأقدام بحثًا عن سبل عيش جديدة ومراعي أكثر خضرة. ذهب البعض إلى حاجر لاميس، وآخرون إلى ميبي، وآخرون إلى نجامينا. وصل الهوسا إلى أراضي سيلسيل بعد وقت قصير من رحيل الفولاني. قاموا بتركيب عدة مضخات مياه وبدأوا سوقًا أسبوعيًا.

في تلك السنوات، فقد أفراد الأسرة أيضًا معظم ماشيتهم بسبب الديدان. دفعت الحاجة إلى شراء الطعام البعض إلى بيع أبقارهم. كما قاموا بتغيير مساراتهم وخططهم المستقبلية. استقر البعض في قرى زراعية، بينما بحث آخرون عن وظائف في المدينة. ومع ذلك، كانت الزاوية في نجامينا ولا تزال مركزًا رئيسيًا يلتقي فيه الفولاني المار ويتبادلون المعلومات. الإسلام هو عامل مهم بين المار، الذين تخلّى الكثير منهم عن حياة الرعي من أجل المدينة، والذين لا يستطيع معظمهم العيش من أرباح رعي الماشية وحدها. المرونة والتغيّر جزءان لا غنى عنهما في مشهد الساحل وسكانه.

نقص المياه المستمر

تمكن الشيخ محمد أزراق من إنشاء مؤسسة دينية كبيرة على الرغم من الصعوبات التي واجهها منذ البداية. لقد جمع الناس معًا، سواء في القرية أو المدينة، أو في الخلوة أو في حقول الرعي. لعب دور الأخ والأب والمعلم في ربط أفراد قبيلة الفولاني المار. علاوة على ذلك، كان مستشارًا ومرشدًا روحيًا خلال الظروف الاقتصادية والسياسية الصعبة التي واجهتها قبيلة ماري فولاني، فضلاً عن البيئة القاسية التي عاشوا فيها. كسكان ريفيين، لجأوا مع ماشيتهم إلى البرك والأحواض والخزانات. مع مرور السنين، أدى الجفاف إلى توقف الإنتاج الزراعي الذي كان يغذي مئات الأشخاص في سيلسيل ونجامينا. حتى الآن، لم يتم استعادة مصدر ثروة مثل سيلسيل بين أفراد هذه العائلة. مع ضغوط تغير المناخ، تتغير دورات المياه في منطقة الساحل ويقوم الفولاني بتعديل مساراتهم وفقًا لذلك. وينتج عن ذلك تبادل مستمر بين المدينة والراعي والمزارع.

السير الذاتية

نشأ سعيد أبو بكر حسين (2001) في نجامينا في ريدينا. تلقى تعليمه في القرآن الكريم تحت رعاية عمه ودرس في جامعة الملك فيصل وجامعة بانديرما في تركيا. لا يزال طالبًا ويعمل مع منظمات خيرية تركية في تشاد. يحب سعيد تاريخ عائلته وسندويشات الشاورما.

لوكا برولز (1994) نشأت في أمستردام في هولندا. درست اللغة العربية والأنثروبولوجيا في جامعة أمستردام وهي حاليًا طالبة دكتوراه في جامعة لايدن. تقوم بأبحاث في تشاد بين معلمات القرآن الكريم وتلاميذهن. لوكا تحب تعلم اللغات وهي نباتية

The rise and fall of a wondrous village

“A jagal amin ragarewal ha Dourbali, minnani hubaru diyam worti ha Cilcilce…The last time we went to Dourbaly, we heard the news that ground water in Cilcile emerged,” says Bint asheikh. She is of the Maare Fulani clan and the one and only daughter of Sheikh Mahamat Azaraq, which has earned her the nickname bint asheikh (the daughter of the Sheikh). She gloats as she relates the story. When she smiles with her dark accentuated lips closed, you can still sense her youthful mischief. Bint asheikh continues: “‘They [the inhabitants of Dourbaly] said: ‘water rose up on the land where your father Sheikh Mahamat Azaraq used to be.’ When we heard the news, we asked our driver to bring us to Cilcile, so that we could see the water of our father. A herder with a walking stick in his hand had stopped there, stomped the ground, and water squirted. Thereafter, people started going to the spring, carrying, drinking, and washing their faces with the water. Among them were the blind, when they washed their faces, their eyes opened. Among them were the ill, whose drinking suddenly healed them. Among them were the paralyzed, who upon drinking and bathing in the water could move. The people in Dourbaly said: ‘We drank from it and we benefited from it.’”

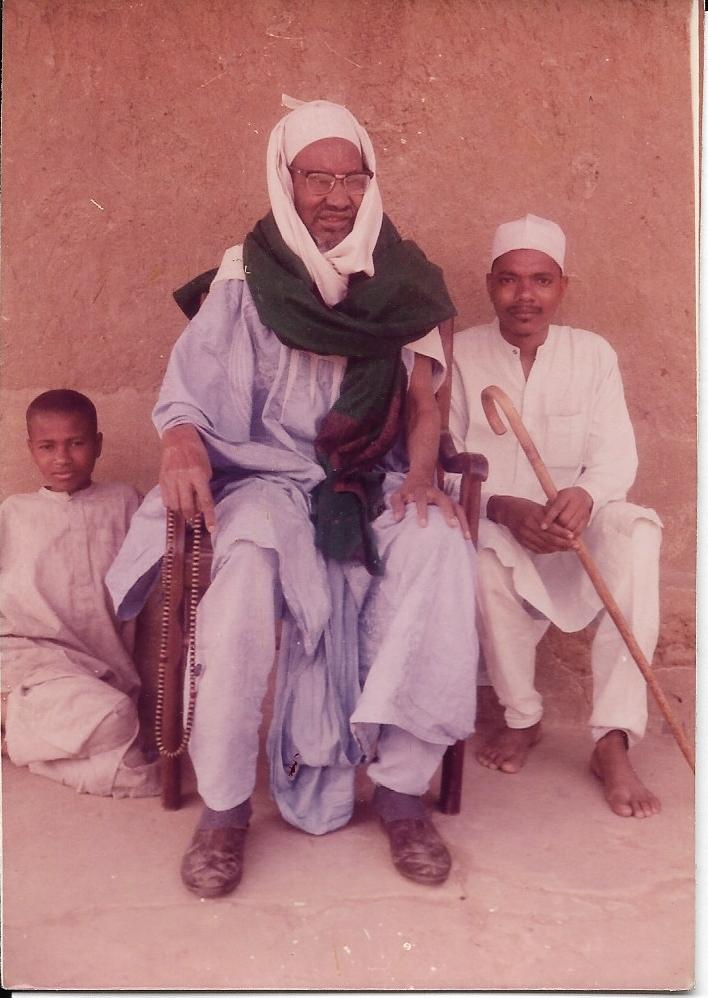

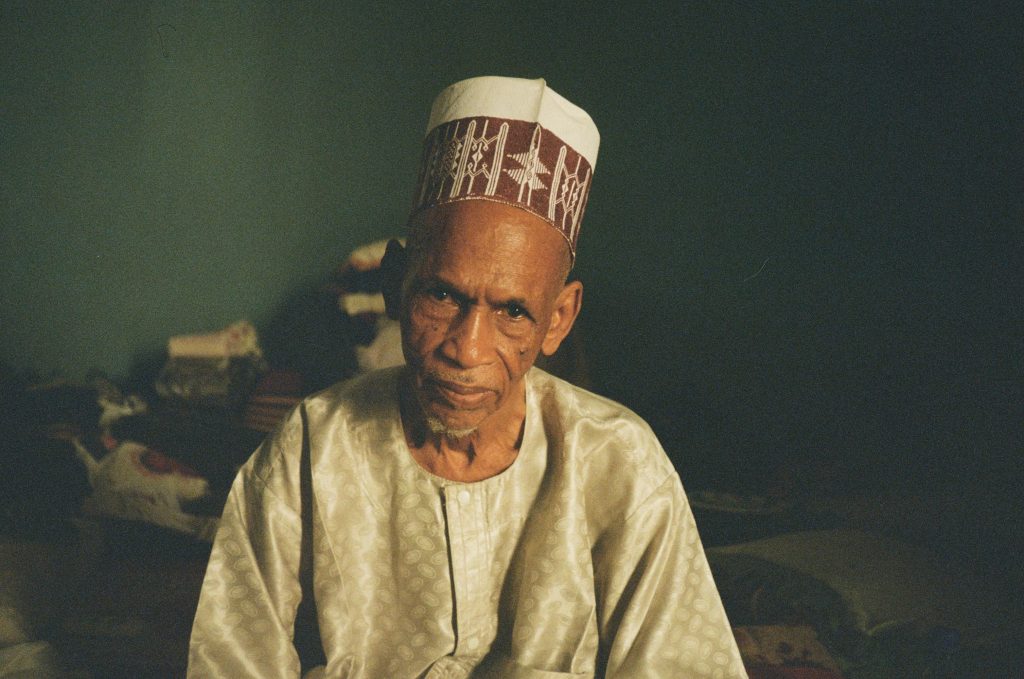

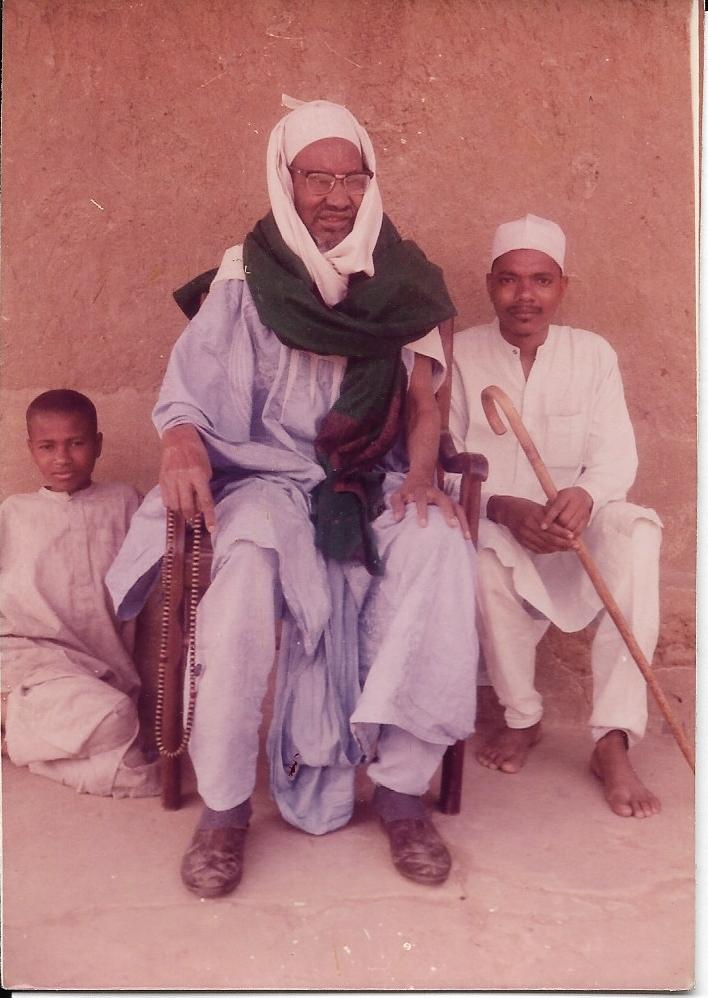

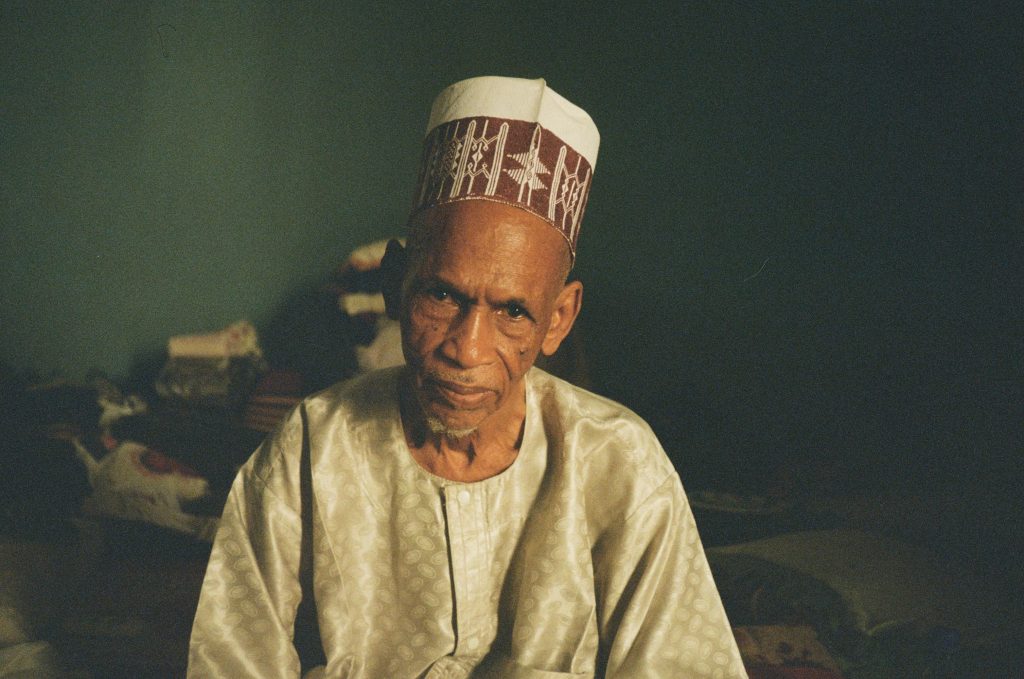

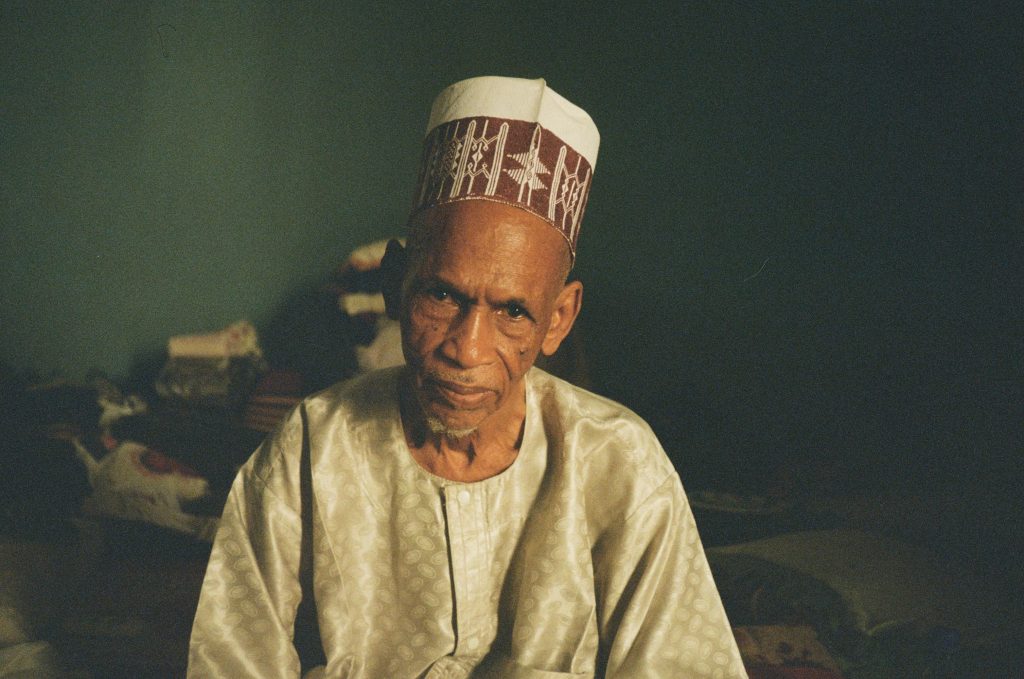

Bint asheikh relates the story sitting in her dark room that is decorated by a glittery pink curtain and dozens of posters of famous Tijani Sheikhs from Nigeria, Senegal, and Cameroon. The room is inside the zawya (meaning, a combined Quran school and mosque). Her father constructed the space in the heart of N’Djaména in 1973. Sheikh Mahamat Azaraq was a religious leader, scholar, herder, and farmer who has roots in Cameroun and Nigeria. He was a follower of the Senegalese scholar Sheikh Ibrahim Niasse and a prominent student of Sheikh Ahmad Abu al-Fatih al-Yarawi in federal Nigeria. In his turn, Sheikh Ahmad Abu al-Fatih was a student of Sheikh Ibrahim Niasse. Sheikh Mahamat Azaraq was a key player in spreading the Tijani order in Chad. He was one of nine sheikhs to whom Sheikh Ahmad Abu al-Fatih sent a letter, granting them absolute authority over the affairs of the religious order in Chad. Sheikh Mahamat Azaraq passed away in 2001, but he has left an ineffaceable mark on a Fulani and Tijani community that finds itself North, East, South, and West of N’Djaména. Communities from Chad to Cameroon and from Nigeria to Senegal know of his deeds and name and believe in the supernatural interference of the Sheikh in the human world. Like Dourbaly’s inhabitants, who taste, feel, and see the water of the magic well that supposedly has healing qualities. The sensory engagement reflects a worldview of a Fulani community in awe and the continued religious significance of the Sheikh. There is more to the miracle. It brings to attention the object of desire, healing water, in a community that has faced health hazards and water shortages since at least the 1950s.

The authors of this article are Said Aboubakar and Luca Bruls, who met each other around the zawya in the tight streets of Chad’s capital N’Djaména. On a late night walk to the bus, Said expressed his wish to write the life story of the Sheikh and the idea came upon us to collaborate. Not long after, we began our search for what turned out to be much more than the account of a man with Islamic credentials. It uncovered the story of a partially urbanized and sedentarized group of Fulani nomads. Due to new living conditions, as well as the poverty they faced, they adapted their social organization and sought for financial stability through agriculture and what N’Djaména had to offer. Young men did business on the market, while women occasionally sold food and objects within households. The knowledgeable Sheikh played a powerful role in these changes. The more he travelled around for Islamic knowledge and the more Quran schools he constructed, the more he became a man with a large social network and considerable power in his community. Family members followed him in his travels and used his guidance to grow out to spiritual leaders themselves. Pastors’ kids came to study in the city, often leaving their future cattle all together. The Sheikh’s biography and the experiences told by his family members show the importance of Islam in a nomadic group adapting to other lifestyles.

We toured the urban zones of N’Djaména, frequenting the various neighbourhoods where a melange of born city dwellers and former herders had settled and memorized the twentieth century’s happenings. We bumped our way to Hadjer Lamis, where the rain coloured the fields green and farmers and families with little left of their troops of red cows welcomed us in their moss bricked houses. We crossed the river in Chari Baguirmi, the stretched out fields showing the remains of corn and wheat cultivated by Fulani farmers. As if collecting the golden grains between the sand, bit by bit women like Bint asheikh and Zahra and men like Khalifa (d. 2025) and Modibo, whom we meet later, related their lively memories. They rarely seized to mention the place name Cilcile. In order to arrive there, Sheikh Mahamat Azaraq faced East…

The migration that brought fame

The Sheikh’s journey began in Walooji, present-day Cameroon, where he was born, raised and set his goals. Fulani have migrated for centuries, in search for the appropriate environment for their livestock and sometimes for security reasons, as is the case with the family of Sheikh Mahamat Azraq. Firstly, this nomadic family entered Chad because the authorities in Cameroon pressured them to pay taxes for their livestock. Secondly, they sought security from robbery and murder. According to a story of one of Sheikh’s servants, Sa’ina, one day a group of supposedly ‘black Frenchmen with Senegalese origins’ killed the Sheikh’s brother. The comment left us wondering what interactions might have preceded this conflict between a herder and the colonial administration. An event that left many disturbed. These conditions made the Sheikh and his family consider to leave the colonized territories. When Sheikh and some brothers heard about the news of the lands around Dourbaly in Chad, they did not hesitate any longer to leave Walooji. Several brothers and their cows had already migrated to Dourbaly around 1947 and they informed the Sheikh’s brothers about the better conditions in Dourbaly, where they did not face theft, taxation, and shedding of innocent blood, as the story of Sa’ina indicates.

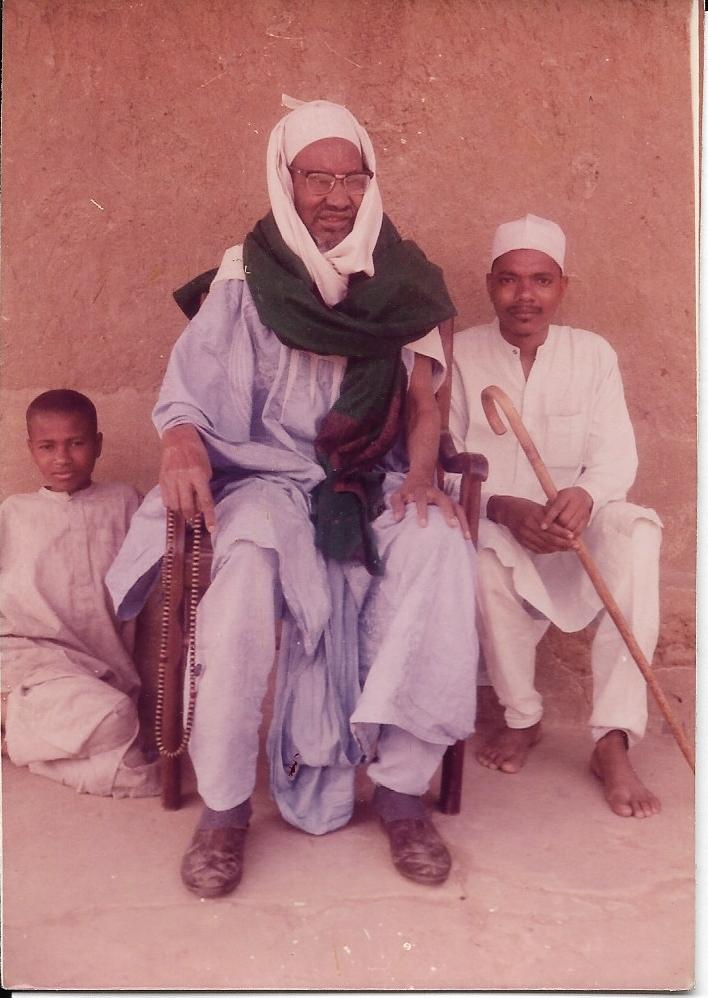

On an early morning in October, we enter the zawya in N’Djaména to do an interview with Khalifa, a cousin of Sheikh Mahamat Azaraq. We find a large group of muhajireen, some rinsing and writing their loha (tableau), others washing their clothes. Their master sits in front of them and performs his teaching roles. When we enter the Sheikh’s salon, we find Khalifa and he invites us into the room of the late Sheikh Mahamat Azraq himself. The room is full of souvenir photos of the sheikhs who used to come to visit Sheikh Mahamat Azraq, including images of Nigerian Sheikh Abu al-Fatih and the sons of Sheikh Ibrahim Niasse from Senegal. We sit ourselves on a carpet, facing a closet full of Islamic scholarly works. When Khalifa tells us the story of the journey his uncles and his father made and the hardships they faced during the march, he seems to be moved. His voice rises and falls, especially when Said tells him: “I can’t believe that you have overcome all this,” and Khalifa responded, “Kay” and shakes his head left and right, as a result of his emotion. Khalifa continues: “It was a very difficult migration where we faced hardships. The distance from Walooji to Dourbaly was large, and the sun was so hot that the soil under our feet felt like embers because we were travelling this distance on foot behind the livestock.”

When the Sheikh finished his studies, he joined them. He found them in Derbaji, a village close to Dourbaly. There, he started teaching the holy Quran to young boys and girls. Since religion has a major influence on the Maare Fulani, the community surrendered their affairs to this man full of Islamic wisdom. The relevance of religion in the community partially has to do with the role its Fulani members believe they played in spreading Islam throughout Africa. The family, first of all, trusted Sheikh Mahamat Azaraq’s clerical and spiritual qualities. He was of their flesh and blood, and so people gave him leadership.

From then on, the Sheikh played a role in the movements and travels of Maare Fulani. Not only did people obey him because they saw violating the Sheikh as a violation of the Sharia. He and his brothers also owned a considerable number of livestock, which is an important factor in the geographical organization of Fulani. In 1952, the Sheikh and his relatives moved to Gawil, an area fifty kilometres away from Derbaji. The land there was rich in grass and ponds, and thus a better spot for the cows they bred. In Gawil, the Sheikh opened his first khalwa, where he only taught the children of his brothers and relatives. Just a few years later a new opportunity arose to migrate to Cilcile in 1957, so Sheikh Mahamat Azaraq and some of his relatives moved, while others stayed behind and continued to run the khalwa.

The well is plenty

From the conversations with Bint asheikh and Khalifa about the years the Sheikh and his relatives spent in Cilcile from 1957 to 1978, it became clear that social life in Cilcile continued to be marked by mobility. People and cattle followed the seasonal whims to make ends meet. When the first rain drops fell in autumn, Maare across the country returned to Cilcile’s soil. The in turban shelled herders who had settled in villages like Hedide around Lac Chad slapped their sticks on the bums of their cows, nearing inch by inch. The muhajireen of Sheikh Mahamat Azaraq, his older students and their wives in N’Djaména, put few possessions in bags and left for the modest state of the village, wishing for a fertile moment. In this village, herders, city dwellers, and farmers of the Maare Fulani met every year when the soil became soppy. Water is an element essential in life, equally so it is a driver for connection. It brings people together.

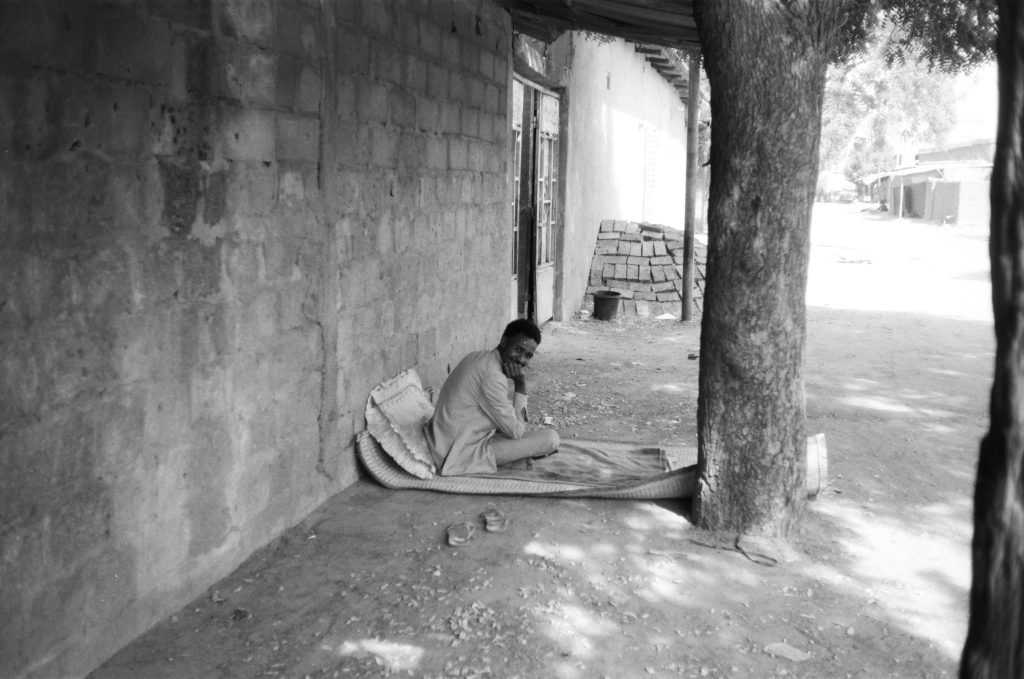

On a tiny veranda with a straw roof in the village Meebi on the riverbanks of the Chari, we meet Modibo. Modibo is 77 years old and was born around Lac Chad. After studying the Quran with Sheikh Mahamat Azaraq in N’Djaména, he decided he wanted to do agriculture and moved to Cilcile, where he stayed all year around. He does not regret his days in the village, but elaborates with a sour heart how the village slowly fell apart. In Cilcile people lived near the well Bir Tourné Moussa Nayn, on the land of a Fulani by the name of Beské. To get water from the well, they walked with their donkeys for an hour. Cow-breeding Arabs, under the reign of Sultan Ahmed Gojal, owned the well. The Arabs lived in another village and frequently came to greet their Fulani neighbours. Modibo relates, “Humma kullo jo fi bakanna. Sabab Sheikh Azaraq da… They all came to our place. Due to Sheikh Azaraq.” He tells how they were like family. “It was due to mahabba (affection) and religion.” The curiosity for the Sheikh thus not only stuck with the Maare Fulani, but also with other ethnic communities. During an interview in Mani Kosam, a village in Hadjer Lamis, Hisseini added that the Sheikh had Arabs and Massa students in Cilcile. Hisseini is a man of 85 with enormous glasses and an abundant charisma, who spend his childhood with the Sheikh in Gawil as a herder. He praises the Sheikh and remembers his incredible smell of sandal wood. We listened to his rasping voice among the soundscape of his bleating goats in Mani Kosam. He loved and still loves the man: “Sheikh was a fukaraku (poor man). But the elders loved the man, because he was a modibo (religious scholar) who knew how to read.” Despite his poverty, Sheikh gained status for himself and his community.

Sheikh undoubtedly imposed Islam wherever he settled. When the Sheikh and his two wives arrived in Cilcile, he taught the children of his brothers and sisters around a fireplace, a habit Sheikh’s descendants in Meebi have held on to. One of his early students, whom like Modibo lives in Meebi, took over the classes in Cilcile when Sheikh left for N’Djaména in the late 50s. The Sheikh became more and more integrated in the urban zones of N’Djaména. Although life was not easy in the poor districts of central N’Djaména, he managed to get by as he gained a bigger Muslim following. Meanwhile, his students in Cilcile sedentarized and became teachers of the Quran. Their means of income changed. Modibo and three others were responsible to cultivate cereals and to read the Quran at night. Their wives focused on the processing of the grains. During the rainy season, they welcomed their cow-breeding relatives and Sheikh’s muhajireen from N’Djaména. The expansion of Islam among Maare Fulani was a driver to adopt an agricultural lifestyle. Because of the rising demand for food crops in the city due to a growing number of students in the 60s, Maare Fulani turned to cultivate food crops to meet the demand.

To this day, on the other side of the road of the zawya lives Zahra. Zahra is 69 years old. Zahra’s lafay hangs loosely over her head. Her long slender hands, characteristic for the tall female herders, touch Luca’s legs as she offers us her perspective on the agricultural activities in Cilcile. In 1968 the newly wed Zahra, a herder daughter, settled in N’Djaména at the age of 12. That same year, she travelled with her husband, another couple, and a half of Sheikh’s muhajireen to Cilcile. Every year, during a period of five years she stayed in Cilcile for six months. She honestly says the days were not easy, together with other women she carried out khidma murr (hard work). Her words carry us away: “Amshi al-mi, yimshi khatab. Niduggu khala bi ideena, nisayyu eish. Da shughl hana ajur bass… Walking to get water, wood. We grained wheat with our hands, we made boule. It was work for ajur.” An Islamic motivation that also echoed in Bint Asheikh’s words: “Agriculture has baraka.” Zahra went to Cilcile because the Sheikh asked her to and she would not refuse a request from him whom she lovingly calls her father. So in the late 60s and early 70s, women in the village prepared food, around 300 students planted grains of wheat, corn, and okra, and harvested when the stalks glistered in the Sahelian sunlight. The moment the rich rains were over, they cleaned out the lands and one responsible man brought half of the yield to N’Djaména. There, the wives and cousins of Sheikh Mahamat Azaraq stored the 30-40 bags inside the zawya, sufficing the Quran students and Maare families in the zawya of food nearly all year around.

Farewell: Changing direction

But the stock did not last. Fatigue thickened in Cilcile. After Zahra left Cilcile, her aunt, one of Sheikh’s wives, moved to Cilcile but died of a severe decease she contracted from the waters. Those left in the village faced increasing water shortages from 1974 to 1978. Many people resorted to eating leaves to cover their hunger. Modibo in Meebi said with a sad face: “Bir da wigif bass, akl ma fi, al-mi ma fi… The well emptied out, there was no food, no water. That has brought us here.” The herders stopped coming with their cows in the rainy season. At the start of the dry season of 1978 the sedentarized group of men, women, children, and cows left Cilcile for good. As soon as the Fulani had arrived, as quick they left by foot in search of new livelihoods and greener pastures. Some went to Hadjer Lamis, others to Meebi, and again others to N’Djaména. Hausa arrived on the soil of Cilcile, not long after the Fulani left. They installed several water pumps and started a weekly market.

Around those years, family members also lost most of their livestock due to worms. The necessity to buy food made some sell their cows. They, as well, altered their routes and future plans. Some settled in agricultural villages, others sought jobs in the city. The zawya in N’Djaména, however, was and continues to be a central hub where Maare Fulani meet and exchange information. Islam is an important carrier among the Maare, of whom many have changed a herder life for the city and of whom the majority cannot only live of the profits of cattle herding. Flexibility and changeability are indispensable parts of the Sahelian landscape and its inhabitants.

Persistent water scarcity

Sheikh Mahamat Azaraq was able to establish a large religious institution despite the hardships he faced from early on. He brought people together, be they in the village or the city, the khalwa or the grazing fields. He played a role as a brother, father, and teacher in connecting members of the Maare Fulani. Moreover, he was an advisor and spiritual guide during the economically and politically difficult circumstances the Maare Fulani faced, as well as the ecologically harsh environments they lived in. As rural dwellers, they sought refuge with their livestock at ponds, basins, and reservoirs. With the years, drought led to the cessation of agricultural production that fed hundreds of people in Cilcile and N’Djaména. Up until now, a source as wealthy as Cilcile has not been restituted among this family. With the pressure of climate change, the water cycles in the Sahel change and Fulani adjust their routes accordingly. This results in a continued exchange between the city, the herder, and the farmer.

Biographies

Said Aboubakar Hussein (2001) grew up in N’Djaména in Ridina. He is schooled in the Holy Quran under the wing of his uncle and studied at the King Faysal University and the University of Bandirma in Turkey. He is still a student and works with Turkish charitable organizations in Chad. Said has a love for his family history and shoarma sandwiches.

Luca Bruls (1994) grew up in Amsterdam in The Netherlands. She studied Arabic language and anthropology at the University of Amsterdam and is currently a PhD candidate at Leiden University. She does research in Chad among female Quran teachers and their students. Luca loves learning languages and is a vegetarian.

Ce blog est rédigé par Said Aboubakkar et Luca Bruls. Il est le fruit de leur participation au projet « Soutien à la rédaction de rapports sur le pastoralisme nomade par la GIZ et Voice4Thought (V4T) », qui ont organisé conjointement un atelier à N’Djaména en 2025.

L’ascension et la chute d’un village merveilleux

«A jagal amin ragarewal ha Durbali, minnani hubaru diyam worti ha Cilcilcile…La dernière fois que nous sommes allés à Dourbaly, nous avons appris que de l’eau souterraine avait fait surface à Cilcile, » raconte Fatma. Elle appartient au clan Maare Fulani et est la fille unique du cheikh Mahamat Azaraq, ce qui lui a valu le surnom de Bint asheikh (la fille du cheikh). Elle se réjouit en racontant cette histoire. Quand elle sourit, les lèvres sombres et accentuées fermées, on devine encore sa malice juvénile. Fatma poursuit : « Ils [les habitants de Dourbaly] ont dit : l’eau a jailli sur la terre où se trouvait ton père, le cheikh Mahamat Azaraq. » Quand nous avons appris la nouvelle, nous avons demandé à notre chauffeur de nous emmener à Cilcile, afin que nous puissions voir l’eau de notre père. Un berger, un bâton à la main, s’était arrêté là, avait frappé le sol du pied et de l’eau avait jailli. Par la suite, les gens ont commencé à se rendre à la source, à transporter, à boire et à se laver le visage avec cette eau. Parmi eux se trouvaient des aveugles qui, après s’être lavé le visage, ont ouvert les yeux. Parmi eux se trouvaient des malades qui, après avoir bu, ont été soudainement guéris. Parmi eux se trouvaient des paralysés qui, après avoir bu et s’être baignés dans l’eau, ont pu bouger. Les habitants de Dourbaly dirent : « Nous en avons bu et nous en avons tiré profit. »

Bint asheikh raconte cette histoire, assise dans sa chambre sombre décorée d’un rideau rose scintillant et de dizaines d’affiches représentant des cheikhs tijani célèbres du Nigeria, du Sénégal et du Cameroun. La chambre se trouve à l’intérieur de la zawya (qui signifie à la fois école coranique et mosquée). Son père a construit cet espace au cœur de N’Djaména en 1973. Le cheikh Mahamat Azaraq était un chef religieux, un érudit, un éleveur et un agriculteur originaire du Cameroun et du Nigeria. Il était un disciple du savant sénégalais Cheikh Ibrahim Niasse et un élève émérite du Cheikh Ahmad Abu al-Fatih al-Yarawi dans le Nigeria fédéral. À son tour, Cheikh Ahmad Abu al-Fatih était un élève de Cheikh Ibrahim Niasse. Cheikh Mahamat Azaraq a joué un rôle clé dans la diffusion de l’ordre Tijani au Tchad. Il était l’un des neuf cheikhs à qui Cheikh Ahmad Abu al-Fatih a envoyé une lettre leur accordant une autorité absolue sur les affaires de l’ordre religieux au Tchad. Cheikh Mahamat Azaraq est décédé en 2001, mais il a laissé une empreinte indélébile sur la communauté peule et tijani qui se trouve au nord, à l’est, au sud et à l’ouest de N’Djaména. Les communautés du Tchad au Cameroun et du Nigeria au Sénégal connaissent ses actes et son nom et croient en l’intervention surnaturelle du cheikh dans le monde humain. À l’instar des habitants de Dourbaly qui goûtent, sentent et voient l’eau du puits magique qui aurait des vertus curatives. L’engagement sensoriel reflète la vision du monde d’une communauté peule en admiration et l’importance religieuse continue du cheikh. Mais le miracle ne s’arrête pas là. Il attire l’attention sur l’objet du désir, l’eau curative, dans une communauté qui est confrontée à des risques sanitaires et à des pénuries d’eau depuis au moins les années 1950.

Les auteurs de cet article sont Said Aboubakar, petit-fils du cheikh Mahamat Azaraq, et Luca Bruls, doctorant travaillant avec la famille du cheikh. Nous nous sommes rencontrés près de la zawya, dans les rues étroites de Ridina, un quartier de N’Djamena, la capitale du Tchad. Lors d’une promenade nocturne vers l’arrêt de bus, Said a exprimé son souhait d’écrire la biographie du cheikh et l’idée d’une collaboration nous est venue. Peu de temps après, nous avons commencé nos recherches, qui se sont avérées être bien plus que le récit d’un homme aux références islamiques. Elles ont révélé l’histoire d’un groupe de nomades peuls partiellement urbanisés et sédentarisés. En raison de leurs nouvelles conditions de vie et de la pauvreté à laquelle ils étaient confrontés, ils ont adapté leur organisation sociale et cherché à atteindre une stabilité financière grâce à l’agriculture et à ce que N’Djaména avait à offrir. Les jeunes hommes faisaient du commerce au marché, tandis que les femmes vendaient occasionnellement de la nourriture et des objets dans les foyers. Le cheikh, qui avait beaucoup de connaissances, a joué un rôle important dans ces changements. Plus il voyageait pour acquérir des connaissances islamiques et plus il construisait d’écoles coraniques, plus il devenait un homme doté d’un vaste réseau social et d’un pouvoir considérable au sein de sa communauté. Les membres de sa famille le suivaient dans ses voyages et suivaient ses conseils pour devenir eux-mêmes des chefs spirituels. Les enfants des pasteurs venaient étudier en ville, abandonnant souvent leur futur bétail. La biographie du cheikh et les expériences racontées par les membres de sa famille montrent l’importance de l’islam dans un groupe nomade qui s’adapte à d’autres modes de vie.

Nous avons visité les zones urbaines de N’Djaména, fréquentant les différents quartiers où un mélange de citadins de souche et d’anciens éleveurs s’étaient installés et avaient mémorisé les événements du XXe siècle. Nous avons pris la route cahoteuse vers Hadjer Lamis, où la pluie avait verdoyé les champs et où les agriculteurs et leurs familles, qui n’avaient plus que quelques vaches rouges, nous ont accueillis dans leurs maisons en briques de mousse. Nous avons traversé le fleuve Chari Baguirmi, où s’étendaient les champs montrant les restes de maïs et de blé cultivés par les agriculteurs peuls. Comme si elles ramassaient les grains dorés entre le sable, petit à petit, des femmes comme Bint Asheikh et Zahra et des hommes comme Khalifa (décédé en 2025) et Modibo Mahamat, que nous avons rencontrés plus tard, nous ont raconté leurs souvenirs vivants. Ils n’ont cessé de mentionner le nom du lieu Cilcile. Pour y arriver, le cheikh Mahamat Azaraq s’est tourné vers l’est.

La migration qui a apporté la renommée

Le voyage du cheikh a commencé à Walooji, aujourd’hui au Cameroun, où il est né, a grandi et s’est fixé des objectifs. Les Peuls ont migré pendant des siècles, à la recherche d’un environnement approprié pour leur bétail et parfois pour des raisons de sécurité, comme c’est le cas de la famille du cheikh Mahamat Azraq. Tout d’abord, cette famille nomade est entrée au Tchad parce que les autorités camerounaises les ont contraints à payer des taxes pour leur bétail. Ensuite, elle cherchait à se protéger contre les vols et les meurtres. Selon le récit d’un des serviteurs du cheikh, Sa’ina Idriss, un jour, un groupe de « Français noirs d’origine sénégalaise » aurait tué le frère du cheikh. Ce commentaire nous a amenés à nous interroger sur les interactions qui ont pu précéder ce conflit entre un éleveur et l’administration coloniale. Un événement qui a bouleversé beaucoup de gens. Ces conditions ont poussé le cheikh et sa famille à envisager de quitter les territoires colonisés. Lorsque le cheikh et certains de ses frères ont entendu parler des terres autour de Dourbaly au Tchad, ils n’ont pas hésité plus longtemps à quitter Walooji. Plusieurs frères et leurs vaches avaient déjà émigré à Dourbaly vers 1947 et ils ont informé les frères du cheikh des meilleures conditions à Dourbaly, où ils n’étaient pas confrontés au vol, à la taxation et au sang d’un innocent versé, comme l’indique l’histoire de Sa’ina Idriss.

Un matin d’octobre, nous entrons dans la zawya de Ridina pour interviewer Khalifa, un cousin du cheikh Mahamat Azaraq. Nous trouvons un grand groupe de muhajireen, certains rinçant et écrivant leur loha (tableau), d’autres lavant leurs vêtements. Leur maître est assis devant eux et dispense son enseignement. Lorsque nous entrons dans le salon du cheikh, nous trouvons Khalifa qui nous invite à entrer dans la chambre du défunt cheikh Mahamat Azraq lui-même. La pièce est remplie de photos souvenirs des cheikhs qui venaient rendre visite au cheikh Mahamat Azraq, notamment des images du cheikh nigérian Abu al-Fatih et des fils du cheikh Ibrahim Niasse du Sénégal. Nous nous asseyons sur un tapis, face à une armoire remplie d’ouvrages savants islamiques. Lorsque Khalifa nous raconte le voyage que ses oncles et son père ont effectué et les difficultés qu’ils ont rencontrées pendant la marche, il semble ému. Sa voix monte et descend, surtout lorsque Said lui dit : « Je n’arrive pas à croire que tu aies surmonté tout cela », et Khalifa répond « Kay » et secoue la tête de gauche à droite, sous le coup de l’émotion. Khalifa poursuit : « Ce fut une migration très difficile, au cours de laquelle nous avons rencontré de nombreuses épreuves. La distance entre Walooji et Dourbaly était grande, et le soleil était si chaud que le sol sous nos pieds semblait brûlant, car nous parcourions cette distance à pied derrière le bétail. »

Lorsque le cheikh a terminé ses études, il les a rejoints. Il les a retrouvés à Derbaji, un village proche de Dourbaly. Là, il a commencé à enseigner le Coran aux jeunes garçons et filles. La religion ayant une influence majeure sur les Maare Fulani, la communauté s’en remit à cet homme plein de sagesse islamique. L’importance de la religion dans la communauté est en partie liée au rôle que ses membres fulani pensent avoir joué dans la diffusion de l’islam à travers l’Afrique. La famille, tout d’abord, faisait confiance aux qualités cléricales et spirituelles du cheikh Mahamat Azaraq. Il était de leur sang et de leur chair, et les gens lui confièrent donc le leadership.

Dès lors, le cheikh a joué un rôle dans les mouvements et les déplacements des Maare Fulani. Non seulement les gens lui obéissaient parce qu’ils considéraient que désobéir au cheikh revenait à enfreindre la charia, mais lui et ses frères possédaient également un nombre considérable de têtes de bétail, ce qui est un facteur important dans l’organisation géographique des Fulani. En 1952, le cheikh et ses proches ont déménagé à Gawil, une région située à cinquante kilomètres de Derbaji. La terre y était riche en herbe et en étangs, ce qui en faisait un meilleur endroit pour les vaches qu’ils élevaient. À Gawil, le cheikh a ouvert sa première khalwa, où il n’enseignait qu’aux enfants de ses frères et de ses proches. Quelques années plus tard, en 1957, une nouvelle opportunité de migrer vers Cilcile s’est présentée. Le cheikh Mahamat Azaraq et certains de ses proches ont donc déménagé, tandis que d’autres sont restés pour continuer à gérer la khalwa.

Le puits est abondant

D’après les conversations avec Bint Asheikh et Khalifa au sujet des années que le cheikh et ses proches ont passées à Cilcile de 1957 à 1978, il est apparu clairement que la vie sociale à Cilcile continuait d’être marquée par la mobilité. Les gens et le bétail suivaient les caprices des saisons pour joindre les deux bouts. Lorsque les premières gouttes de pluie tombaient à l’automne, les Maare de tout le pays retournaient sur les terres de Cilcile. Les bergers en turban qui s’étaient installés dans des villages comme Hedide, autour du lac Tchad, frappaient leurs bâtons sur les fesses de leurs vaches, qui s’approchaient petit à petit. Les muhajireen de Sheikh Mahamat Azaraq, ses élèves les plus âgés et leurs épouses à N’Djaména, ont mis quelques affaires dans des sacs et sont partis pour le modeste village, dans l’espoir d’une période fertile. Dans ce village, les éleveurs, les citadins et les agriculteurs des Maare Fulani se réunissaient chaque année lorsque le sol devenait détrempé. L’eau est un élément essentiel à la vie, mais elle est aussi un moteur de connexion. Elle rassemble les gens.

Sur une petite véranda au toit de paille dans le village de Meebi, sur les rives du Chari, nous rencontrons Modibo Mahamat. Modibo a 77 ans et est né près du lac Tchad. Après avoir étudié le Coran avec Cheikh Mahamat Azaraq à N’Djaména, il a décidé de se lancer dans l’agriculture et s’est installé à Cilcile, où il est resté toute l’année. Il ne regrette pas ses jours passés dans le village, mais raconte avec amertume comment celui-ci s’est lentement délabré. À Cilcile, les gens vivaient près du puits Bir Tourné Moussa Nayn, sur les terres d’un Peul du nom de Beské. Pour aller chercher de l’eau au puits, ils marchaient pendant une heure avec leurs ânes. Sous le règne du sultan Ahmed Gojal, le puits appartenait à des Arabes éleveurs de vaches. Les Arabes vivaient dans un autre village et venaient souvent saluer leurs voisins peuls. Modibo raconte : « Humma kullo jo fi bakanna. Sabab Sheikh Azaraq da… Ils venaient tous chez nous. Grâce à Sheikh Azaraq. » Il explique qu’ils étaient comme une famille. « C’était grâce à la mahabba (affection) et à la religion. » La curiosité pour le cheikh ne s’est donc pas limitée aux Maare Fulani, mais s’est également étendue à d’autres communautés ethniques. Lors d’une interview à Mani Kosam, un village de Hadjer Lamis, Hisseini a ajouté que le cheikh avait des étudiants arabes et massa à Cilcile. Hisseini est un homme de 85 ans, portant d’énormes lunettes et doté d’un charisme débordant, qui a passé son enfance avec le cheikh à Gawil en tant que berger. Il fait l’éloge du cheikh et se souvient de son incroyable odeur de bois de santal. Nous avons écouté sa voix rauque parmi les bêlements de ses chèvres à Mani Kosam. Il aimait et aime toujours cet homme : « Le cheikh était un fukaraku (homme pauvre). Mais les anciens l’aimaient, car c’était un modibo (érudit religieux) qui savait lire. » Malgré sa pauvreté, le cheikh a acquis un statut pour lui-même et sa communauté.

Le cheikh a sans aucun doute imposé l’islam partout où il s’est installé. Lorsque le cheikh et ses deux épouses sont arrivés à Cilcile, il a enseigné aux enfants de ses frères et sœurs autour d’un feu de cheminée, une habitude que les descendants du cheikh à Meebi ont conservée. L’un de ses premiers élèves, Yahya, qui comme Modibo Mahamat vit à Meebi, a repris les cours à Cilcile lorsque Sheikh est parti pour N’Djaména à la fin des années 50. Sheikh s’est de plus en plus intégré dans les zones urbaines de N’Djaména. Bien que la vie n’ait pas été facile dans les quartiers pauvres de Marjan Daffak et Ridina, il a réussi à s’en sortir en gagnant un plus grand nombre de fidèles musulmans. Pendant ce temps, ses élèves de Cilcile se sont sédentarisés et sont devenus des enseignants du Coran. Leurs moyens de subsistance ont changé. Yahya, Modibo Mahamat et deux autres étaient chargés de cultiver des céréales et de lire le Coran la nuit. Leurs épouses se concentraient sur la transformation des céréales. Pendant la saison des pluies, ils accueillaient leurs parents éleveurs de vaches et les muhajireen du cheikh de N’Djaména. L’expansion de l’islam parmi les Maare Fulani a été un facteur déterminant dans l’adoption d’un mode de vie agricole. En raison de la demande croissante de cultures vivrières dans la ville due à l’augmentation du nombre d’étudiants dans les années 60, les Maare Fulani se sont tournés vers la culture vivrière pour répondre à la demande.

À ce jour, de l’autre côté de la route de la zawya à Ridina, vit Zahra. Zahra a 69 ans. Le lafay de Zahra pend librement sur sa tête. Ses longues mains fines, caractéristiques des grandes éleveuses, touchent les jambes de Luca tandis qu’elle nous donne son point de vue sur les activités agricoles à Cilcile. En 1968, Zahra, jeune mariée et fille de berger, s’est installée à N’Djaména à l’âge de 12 ans. La même année, elle s’est rendue à Cilcile avec son mari, un autre couple et la moitié des muhajireen du cheikh. Chaque année, pendant cinq ans, elle a séjourné à Cilcile pendant six mois. Elle avoue honnêtement que les journées n’étaient pas faciles, car avec d’autres femmes, elle effectuait le khidma murr (travail pénible). Ses paroles nous transportent : « Amshi al-mi, yimshi khatab. Niduggu khala bi ideena, nisayyu eish. Da shughl hana ajur bass… Marcher pour aller chercher de l’eau, du bois. Nous moulions le blé à la main, nous faisions du pain. C’était un travail pour ajur. » Une motivation islamique qui trouvait également un écho dans les paroles de Bint Asheikh : « L’agriculture a baraka. » Zahra est allée à Cilcile parce que le cheikh le lui avait demandé et qu’elle ne pouvait refuser une demande de celui qu’elle appelle affectueusement son père. Ainsi, à la fin des années 60 et au début des années 70, les femmes du village préparaient la nourriture, environ 300 étudiants plantaient des graines de blé, de maïs et de gombo, et récoltaient lorsque les tiges brillaient sous le soleil sahélien. Dès que les pluies abondantes cessaient, ils nettoyaient les terres et un homme responsable apportait la moitié de la récolte à N’Djaména. Là-bas, les épouses et les cousines de Cheikh Mahamat Azaraq stockaient les 30 à 40 sacs dans la zawya, ce qui suffisait à nourrir les étudiants du Coran et les familles Maare de la zawya pendant presque toute l’année.

Adieu : changement de direction

Mais les réserves ne durèrent pas. La fatigue s’accrut à Cilcile. Après le départ de Zahra, sa tante, l’une des épouses du cheikh, s’installa à Cilcile, mais mourut d’une grave maladie contractée à cause de l’eau. Ceux qui restèrent dans le village furent confrontés à des pénuries d’eau croissantes entre 1974 et 1978. Beaucoup de gens en vinrent à manger des feuilles pour apaiser leur faim. Modibo Mahamat, à Meebi, a déclaré avec tristesse : « Bir da wigif bass, akl ma fi, al-mi ma fi…Le puits s’est vidé, il n’y avait plus de nourriture, plus d’eau. C’est ce qui nous a amenés ici. » Les éleveurs ont cessé de venir avec leurs vaches pendant la saison des pluies. Au début de la saison sèche de 1978, le groupe sédentaire composé d’hommes, de femmes, d’enfants et de vaches a quitté Cilcile pour de bon. Aussitôt arrivés, les Peuls sont repartis à pied à la recherche de nouveaux moyens de subsistance et de pâturages plus verts. Certains sont allés à Hadjer Lamis, d’autres à Meebi, et d’autres encore à N’Djaména. Les Haoussas sont arrivés sur le sol de Cilcile peu après le départ des Peuls. Ils ont installé plusieurs pompes à eau et ont lancé un marché hebdomadaire.

À cette époque, les membres de la famille ont également perdu la plupart de leur bétail à cause des vers. La nécessité d’acheter de la nourriture a poussé certains à vendre leurs vaches. Eux aussi ont modifié leurs itinéraires et leurs projets d’avenir. Certains se sont installés dans des villages agricoles, d’autres ont cherché du travail en ville. La zawya de N’Djaména, cependant, était et reste un lieu central où les Maare Peuls se rencontrent et échangent des informations. L’islam est un vecteur important parmi les Maare, dont beaucoup ont troqué la vie de berger contre la ville et dont la majorité ne peut vivre uniquement des profits tirés de l’élevage. La flexibilité et la capacité d’adaptation sont des éléments indispensables du paysage sahélien et de ses habitants.

Pénurie d’eau persistante

Cheikh Mahamat Azaraq a réussi à créer une grande institution religieuse malgré les difficultés auxquelles il a été confronté dès le début. Il a rassemblé les gens, qu’ils soient au village ou en ville, dans la khalwa ou dans les pâturages. Il a joué un rôle de frère, de père et de professeur en mettant en relation les membres des Maare Fulani. De plus, il a été un conseiller et un guide spirituel pendant les périodes économiques et politiques difficiles que les Maare Fulani ont traversées, ainsi que dans les environnements écologiques hostiles dans lesquels ils vivaient. En tant qu’habitants des zones rurales, ils cherchaient refuge avec leur bétail près des étangs, des bassins et des réservoirs. Au fil des ans, la sécheresse a entraîné l’arrêt de la production agricole qui nourrissait des centaines de personnes à Cilcile et à N’Djaména. Jusqu’à présent, aucune source aussi riche que Cilcile n’a été restituée à cette famille. Sous la pression du changement climatique, les cycles de l’eau au Sahel changent et les Peuls adaptent leurs itinéraires en conséquence. Il en résulte un échange continu entre la ville, les éleveurs et les agriculteurs.

Biographies

Said Aboubakar Hussein (2001) a grandi à N’Djaména, dans le quartier de Ridina. Il a suivi une formation sur le Coran sous l’égide de son oncle et a étudié à l’université King Faysal et à l’université de Bandirma en Turquie. Il est toujours étudiant et travaille avec des organisations caritatives turques au Tchad. Said est passionné par l’histoire de sa famille et adore les sandwichs shoarma.

Luca Bruls (1994) a grandi à Amsterdam, aux Pays-Bas. Elle a étudié la langue arabe et l’anthropologie à l’université d’Amsterdam et est actuellement doctorante à l’université de Leyde. Elle mène des recherches au Tchad auprès de femmes enseignantes du Coran et de leurs élèves. Luca adore apprendre les langues et est végétarienne.